By Mohamed Omar Hashi

December 26, 2017

While absence of effective governance continues to dominate the news in Somalia, the long-running political crisis in this war-ravaged country has taken a turn for the worse. The federalisation efforts and federal member state formation process is facing a serious political stalemate. A mishandling of the state formation crisis has proven to be detrimental to the previous federal government’s incipient democratic process and political participation efforts. By October 9, 2016 a new federal member state had been formed, covering the Hiiraan and Middle Shabelle regions, which became known as Hirshabelle. The Government justified its federalisation decision under the pretext of meeting the demands of the people for federalism, arguing that it was simply implementing the will and wish of the people. However, in reality, the people were in no mood to embrace the new state.

The process of federalisation was marked by a number of failures, involving a lack of consultation, political representation, and participation. It has been described as a federal tug of war, in which the members of the federal government, in spite of great opposition from the Hiiraan citizens, comprising civil society, youth, business and women, as well as traditional leaders including Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif, expressed their strong opposition. They questioned the legitimacy of the inter-regional state formation conference in the city of Jowhar, accusing it of defying the aspirations, and challenging the political representations and participation of their people in the country’s post-conflict reconciliation and reunification process.

Of the eight regions that originally made up the independence division, Hiiraan is the only region which remained undivided and retained its initial boundaries. In 2012, the head committee of the assembly of 825 Somali elders formulated a constituent constitution, and suggested that Hiiraan should be awarded a special status because of the ‘special conditions’ of it being the sole survivor of the original eight regions. This recommendation was a means of complying with the Constitutional prerequisite that a ‘federal state’ be formed of two or more regions. This argument was further strengthened by the Galmudug and Puntland administrations case, which were given the privilege to continue sharing Galkayo city and the Mudug region, despite the ongoing debate regarding whether the provisional constitution allows federal states to share a region. The argument is thus that if an exception can be made for Galmudug and Puntland, Hiiraan can make a similar claim.

This showed the disparity in the way federalisation, in different regions of the country, was managed, one rule for one region and another for the rest. Rather than acknowledging the broad and uncontainable disapproval of the people of the region, the former government decided to pursue its unpopular and unsuccessful strategic objectives and, consequently, was able to obtain a kind of pseudo-consent, the delusion of consultation, objectivity and transformed condition. The marginalisation of the Hiiraan traditional elders as well as the fervent celebrations that accompanied the creation of Hirshabelle on 9th October, 2016 in Jowhar confirm the extent of the delusion. Hiiraan was neglected and marginalised and, predictably, soon after the formation of the state, a political meltdown ensued, which demonstrated the flaws in the process, pointing to the enormous challenges the new state now faces. This article will analyse the failed transition to a federal member state from a number of angles. Retrospectively, it will examine the executive orders that were issued, and the power sharing formula and legitimisation efforts that were implemented. Prospectively, the article will discuss the future from a post-state formation perspective, and suggest ways to minimise the potential damage - culminating with some concluding remarks and recommendations.

FEDERALISATION THROUGH POLITICISED EXECUTIVE ORDERS

This section will explore the executive orders or presidential decrees that were issued over several years concerning the formation of the Hiiraan region as a state, in chronological order. This analysis will discuss the main tenets of each executive order, and discusses the underlining motives.

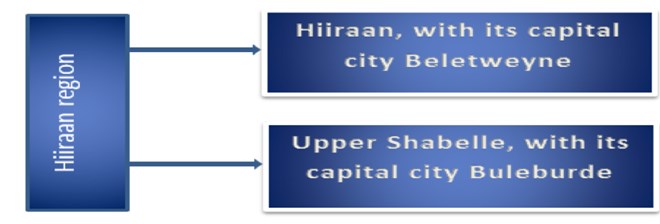

The first wave of executive orders were issued by the former President of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, on July 23, 2012, which partitioned the Hiiraan region into two regions, thus enabling the formation of a joint member-state without violating Article 49(6) of the provisional constitution stipulating that federal states must be comprised of two or more regions. As such, the president used the executive order to alter the number of regions from 18 to 19.

Figure 1: President executive order (Hiiraan region)

Source: /images/2014/Nov/Upper_Shabelle.pdf

However, the president made a U-turn and, on August 1, 2012, just a month after his executive order, the country’s provisional constitution was created, and, contrary to the executive order, the constitution did not indorse the new regions, as such the it upholds 18 contrary to the 19 regions.

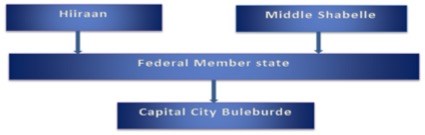

With the country’s election looming, members of parliament were nominated by traditional elders and, by September 16, 2012, the MPs had elected a president. The Federal Government of Somalia was led by the new President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. The new leader had his own political vision and, as such, the region was again subjected to a second wave of state formation executive order, issued on August 6, 2013.

Figure 2: President executive order: Federal Member state formation (Hiiraan and Middle Shabelle)

Source: http://mudug24.com/2015/12/20/dhageyso-madaxweynaha-somalia-oo-goor-dhow-magacaabay-caasimada-hiiraan-iyo-shabellaha-dhexe-iyo-halka-lagu-qabanayo-shirka-maamulka/

From a legal perspective, it is not possible to simply ignore the executive orders that were authorised by the previous presidents. Sheikh Sharif bypassed his own executive order, and President Hassan side-lined presidential decree issues by his predecessor without revoking or amending in order for the heads of executive departments and agencies to rescind the orders, rules, guidelines, and policies that implemented the previous executive orders.

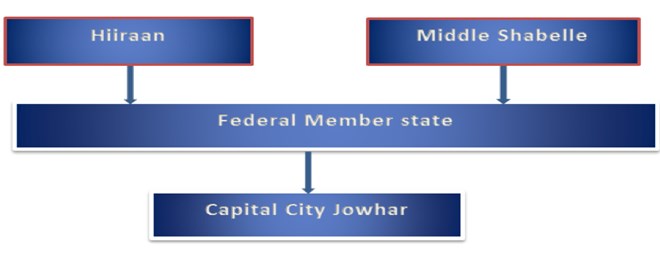

To make matters worse, just three years later, President Hassan issued another executive order, ignoring not only his predecessor’s decree but ironically his own executive order (August 6, 2013) without any amendment, and began lobbying, sponsoring and facilitating for a new phase, by holding state formation conference in Jowhar – leading to a third wave of state formation, based again on a new formula.

Figure 3: Federal Member state formation (Hiiraan and Middle Shabelle)

Source: https://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/manipulated-electoral-process-escalates-inter-clan-conflict

As mentioned, Hassan Sheikh bypassed both his predecessor’s and his own decrees, without revoking, modifying, or superseding his own orders or those issued by his predecessor, ignoring the country’s legislative process and instead making up the rules himself. These failures brought to the surface many unanswered questions regarding the proper use, and abuse, of executive orders. Any president has the authority to issue executive orders, but according to the Constitution, such executive orders cannot be used to change state boundaries, or decree on issues pertaining to decentralisation. To silence opponents, the government took a number of other actions in order to appease key stakeholders, the citizens of the Hiiraan region, and most notably the traditional leader Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif, who were excluded from the initial group of 135 elders responsible for selecting the electoral college of electors.

The state formation doctrines of both presidents were characterised by bureaucratic bulldozing, rather than legislative transparency. Parliament had no say on the state formation process, and the presidents believed exactly that, using executive orders to create a new federal member state, one that served their strategic and political interests but lacked any broad-based support. It is these contradictory events and lack of genuine and creditable political engagement that led to the isolation and alienation of the region; thus, Hiiraan has rightfully expressed its objection and vetoed the most recent formation efforts.

The 1960 constitution was a centralised unitary state system, and that it is because of that system that the ruling elite was able to abuse its power. In order to avoid a potential repeat of this abuse, Somalia adopted a federal system. To endorse the federal system, both presidents cited several clauses to support their executive orders, guided by the principles of decentralisation and federalisation of power, and others that empowered the president to oversee executive institutions and amend the constitution. However, these overlapping and conflicting decrees constitute an egregious violation of the Constitution. Decentralisation and federalisation cannot be achieved through executive orders, which is a central decision, as it runs contrary to the decisions to decentralise. A president would not be able to decentralise through an act that further concentrates power in the centre.

To foresee the future, the question to be addressed revolves around what damage is done to the region, and to an already fragile federal and democratic system, when presidents can unilaterally make policy -any policy - without the consent of parliament. What possible justification is there for the implementation of laws without due regard to the normal legislative process? In short, there is no justification, and no emergency so great that it requires that parliament be completely disregarded. The best way to protect the nation from arbitrary rule is to demand that officials remain true to the democratic legislative process outlined in the Constitution.

POWER-SHARING AND LEGITIMISATION FORMULA

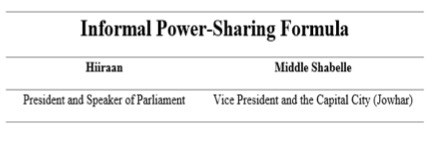

Hirshabelle power-sharing arrangements have failed in several regards. From the onset there was no acceptance of the political settlement, and the mechanisms by which the settlement was attained were illegitimate. The administration supported a failed power sharing formula, a face-saving mechanism to evade a worse consequence, however, astoundingly, this was devoid of any involvement of representatives of the Hiiraan region. The subsequent unwritten power sharing formula was implemented:

Figure 4: Informal Power-Sharing

Power and legitimacy are interconnected concepts. Legitimacy is not something distinct from power; rather, it is one of the key sources of power. If power informs the development as well as the nature of state creation, then legitimacy is a key factor affecting the building, maintaining, as well as the suspension of these kinds of orders. Power-sharing rules, including equal legislative representation across the two regions, are still not yet officially established. This demonstrates the lack of will to formalise power-sharing. There have been a number of failures relating to the power-sharing agreement, not merely the formula, but rather the process followed to achieve such a geometry, which dictates the legitimacy or illegitimacy of its existence. To a large extent, the traditional leaders are the gatekeepers of the fate of the country, and the social life of the people in every imaginable facet. Taking into account the present security and political environment of the nation, and citizens’ restricted influence as well as participation, the traditional leaders are the glue that connects the broken pieces of the nation and supports the legitimacy of the Federal Government. From early in the course of the formation of the Hirshabelle state, the preceding administration took various steps to marginalise the political and social profile of the interests of the citizens of the Hiiraan region.

A united Hiiraan Elders Commission, led by Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif, a prominent leader from the Hiiraan region, suggested the facilitation of a Reconciliation Conference as well as partition of the region into Hiiraan and Upper Shabelle, and, beyond that, the likelihood of creating an interregional state, Middle Shabelle. On the Government’s part, the motive for state creation, and specifically to form the new member state prior to the national presidential election due to take place on February 8, 2017, was driven by a political objective. This objective was the gaining of political allies for the upcoming presidential election. The previous president, Hassan Sheikh, was campaigning for a second term in office, and rushed to finalise an inefficient and clumsy state formation process in the region, hosting a state formation ceremony in Jowhar while marginalising the demands of Hiiraan elders. To legitimise the process, much effort was made to buy the support of the Hiiraan people, and obtain support through other divisive means, which ultimately resulted in the formation of Hirshabelle, with Ali Osoble assigned as its new leader.

In a public speaking engagement in Beledweyne, Ugaas Xasan stated that he was against the formation of the state of Hirshabelle because its citizens had mostly been kept away from the political process. “We were barred from selecting our members of parliament and our rights. Peace was rejected; uniting the people was rejected; someone is uniting the people and another is disuniting them.” Delegates and candidates from the Hiiraan region were prevented from entering the election halls while voting was ongoing, in an attempt to secure a win for the opponents. The alleged misstatement and corruption extended beyond the state formation; the newly appointed leaders of Hirshabelle were accused of resorting to vote buying, fraud, intimidation and getting themselves elected - further isolating the region. It is clear that policy-makers entirely mishandled the region and misjudged their own capacity to lead the country. These variables fuelled a legitimacy crisis, and it is short-term political interests that now continue to hinder the new state.

Due to the deficiency of trust, which characterises the behaviour of the federal government as well as the activities of the newly formed member state, leaders in Hiiraan are reluctant to accept informal arrangements and demand the formalisation of the current power sharing formula. This is because the Hirshabelle power-sharing arrangements were designed without direct or indirect representation of or participation from the people of Hiiraan, leading to a lack of consociationalism. Consociationalism is based on the principle of inclusivity: its ultimate objective is to ensure the extensive inclusion of all stakeholders in governing procedures, and that they are included on their own terms. In this way it aims at direct political representation for all groups. It is a form of direct power sharing because the groups participating in the process of joint decision-making are often clearly identifiable; that is, the diverse groups function as building blocks in the design of political institutions. In the case of Hirshabelle, the consociationalism framework is clearly not being applied.

A NEW ADMINSTRATION: NEED FOR A RADICAL CHANGE

The early enthusiasm over Hirshabelle’s statehood status quickly expired as the huge task ahead became clear. Consequently, Hirshabelle must address numerous unresolved issues before they can formally close their statehood chapter. Despite the scale of the task, it is possible to find solution; however, that would require political investment. Hirshabelle has selected a new leader, Mohamed Abdi Ware, a well-known former Somali government official, Indiana University graduate and a veteran United Nations technocrat. Mohamed vowed to achieve a lasting solution to the dysfunctional political situation of the region, including its contentious federalisation project.

The citizens of Hiiraan believe that from the beginning of the state-building process they were excluded from the political settlement. Therefore, the best way to ease the tension and respond to their grievances is to adopt a re-engagement policy, including traditional leaders in the political course. To enact this, the new administration must adopt a consociationalism power-sharing system. Power sharing will ensure equal regard to all groups, which would suggest that the state is obliged to treat all groups in a rational and respectful manner in exchange for their acceptance of the legitimacy of the political institute. These kinds of mechanisms will serve the dual purpose of promoting post-division unity as well as serving as a basis for future developments in promoting democratic institutions.

The newly elected administration should confront all forms of political polarisation, by pushing for political consensus, supporting reconciliation, and combating electoral fraud. It is recommended that the new administration engage in consultations that support inclusive political reconciliation in a clear, transparent way, and processes that are critical to the legitimisation process. There is a need to establish a new social contract and to include new actors in existing settlements. This is a call to broaden the political process, in light of the necessity to ensure broader representation as well as accountability in the political process.

In these consultations, prospects for the renegotiation of the state-citizens’ relationship, and the need for a political settlement to channel social expectations, should be acknowledged as the core of the political process. The consultations should emphasise the need to support an inclusive political settlement that facilitates constructive state-society relations as state-building priorities. Inclusive politics and participation must be at the centre of efforts to address the root causes of conflict. Dialogue about the political process will promote a climate of respect, and establish a positive environment within which it will be possible to find common ground, and identify a long-term solution for the region.

FURTHER POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

To summarise this article, political processes are the instruments through which relations between state and society are arbitrated, and deals are struck and institutionalised. Political settlements as well as procedures form the rubric of economic, political, as well as social exchange. Since the creation of Hirshabelle, a combination of personal and narrow interests, and a striking lack of credibility from the federal government level, have led to a series of failures, and the prediction of future problems to come. The abuse of presidential power to issue executive orders and other directives, and to implement important administration policies, enabled the previous governments to use this power as it pleased, showing a lack of respect for the constitutional responsibilities. What remains at the centre of the storm, and directing the Hirshabelle ship toward the abyss, is the federal member state’s failed policies, the informal power-sharing formula, and the accompanying Constitution, which was close to failure due to the objections of the Hiiraan people.

Rather than endorsing consociational politics, which aims to achieve political unity, the power-sharing formula applied in Hirshabelle has, until now, created a discord that is wreaking havoc on a very fragile body politic and causing divisive uncertainty. There must be a shift away from the present political practices, which are often coercive, and are characterised by a deep lack of trust and willingness to cooperate. Political institutions can only help unite a society if they arise from existing social forces, and if they represent the real interests and real conflicts in that society. This should then lead to the formation of mechanisms, administrative rules, and measures that are adept at resolving those conflicts and serving those interest.

Hirshabelle must adopt a “formal power-sharing and re-legitimation policy”; it must embrace consociationalism, which is a socially created, continuous process driven by politics, persuasion and power relations, to enable the prospect of peace, reconciliation, and unity. Fundamentally, what is required is a transition from the previous administration’s divisive tactics, spearheaded by a set of highly personalised relations in which individuals and groups seek access to ad hoc benefits, toward a system of transparent, institutionalised relationships.

We call for the current power-sharing (please see Figure 4) to be legally binding and be formalised as this will assist the state overcome previous failures (please see Figure 1, 2, 3), existing obstacles and help shape the expectations of stakeholders, especially those in the Hiiraan region - comprising the civil society, youth, business and women, as well as traditional leaders including Ugaas Xasan Ugaas Khaliif, regarding Hirshabelle’s prospects as a state. We believe formal power sharing will freeze the stalemate and the uncertainty about the outcome of a future political crisis - influencing stakeholders by inducing power sharing behaviour and by shaping expectations for the future. If a pragmatic solution is not found to this political crisis, there will be no lasting solution.

Mohamed Omar Hashi was a Member of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia from 2009 to 2012, and holds an M.A. in International Security Studies from the University Of Leicester.

E-mail: [email protected]