Friday June 14, 2024

By Sébastien Gray

Somalian President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud pictured with Kenyan President William Ruto in the State House in Nairobi, Kenya, on April 11th, 2024 (Photo from PCS).

Somalia’s legacy as a failed state has provided it with a long-lasting negative image on the world stage. While some of the problems which prompted Somalia to be struck with this designation still permeate today, the nation has made significant progress on the path toward recovery and has today escaped the ‘failed state’ designation, though Somalia is still considered to be fragile.

Marred by instability, natural disasters, separatism, and militancy for much of its post-independence history, Somalia’s present situation is the result of a series of complex events that have influenced Somali politics, economics, and society. The largest of these events is the Somali Civil War, ongoing in essence since 1981.

Somalia’s path to recovery from the high levels of destruction the country has witnessed has been a long and difficult one. And while it is far from over, there are several recent events that clearly evidence Somalia’s resilience as a nation and path to stability.But how did this all begin? Much of Somalia’s recent history can be directly traced to the legacy of one man.

The Dictator of Somalia: The 30-Year Power Vacuum

A look at Somalia half a century ago shows a very different situation than what we see today. Fifty years ago, Somalia was ruled by Major General Siad Barre, the former military dictator of Somalia who led Somalia during some of its most stable and successful times, and also some of its darkest.

The administration of Siad Barre (1969-1991) began with progress and modernization for Somalia and its institutions and infrastructure, and ended with war, genocide, and the destruction of significant portions of the nation.

Barre headed a Marxist-Leninist government that aligned itself with the Soviet Union and enjoyed great levels of military, financial, and political support from them.

In the first half of Barre’s rule, Somalia’s literacy rates shot up from less than 5 percent to over 60 percent, Somalia’s first university was built, Mogadishu, the capital, was modernized and road networks were built throughout the nation. In addition, a tree planting campaign took place nationwide to prevent sand dunes from swallowing towns and agriculture, and to reduce the threat of hunger.

Barre’s administration, which was already restrictive in many ways, took a turn for the worse after Somalia’s resounding defeat in the Ogaden War. Beginning in 1977, Barre invaded Ethiopia, also a Marxist-Leninist state, seeking to incorporate Somali lands into a “greater Somalia.”

Barre’s popularity in Somalia soared as the invasion was, initially, a success. Barre successfully seized most of Ethiopia’s Somali regions. However, the invasion was unpopular with the Soviets. The USSR pulled their support from Somalia, and instead gave it to Ethiopia, assisting them in repelling the invasion. Cuba also offered significant support to Ethiopia, including deploying 12,000 soldiers to support Ethiopia’s war effort.

The war ended in March of 1978. By the end of the war, Somalia’s military was decimated, with a third of Somalia’s regular troops being killed, and half of their air force destroyed.

Somalia was defeated, and Barre’s regime became increasingly unpopular. Barre quickly turned to authoritarian measures, including targeting some specific Somali clans he accused of dissent, in order to cling to power.

The rebellion which began after Somalia’s defeat and Barre’s subsequent crackdowns within years escalated into civil war. Crackdowns reached a peak in 1987, with Barre carrying out the Isaaq genocide, which killed between 50,000 to 200,000 civilians, and left many cities, mostly in Somaliland in the north, destroyed.

As a part of the civil war, Barre’s regime fell in 1991. Barre held such a level of control over the state that his toppling left a massive power vacuum, which has yet to be filled entirely by any individual or government. Notably, 1991 was also when Somaliland declared independence from Somalia. Somaliland remains de-facto independent to this day.

Somalia’s present government has proven to be the dominant force in the current era of the civil war, but it maintains nowhere near the level of total control Barre maintained during his administration. The race to fill the power vacuum created by the fall of Barre’s administration is one that has been undertaken by many, and has been a primary factor in the creation of many of Somalia’s present issues.

Moments of Marginal Success

As mentioned, Somalia still faces a number of significant issues that prevent the nation from achieving its true potential, and from being a stable nation with strong institutions. But as Somalia now is far different from itself 50 years ago, it is also different from itself five, ten, and 20 years ago.

In recent years in particular, Somalia has made several notable gains in recovering from the lasting effects of its ongoing civil war.

While a long process, this progress can be evidenced by several recent events:

- Significant gains in the fight against Al-Shabaab, as a testament of Somalia’s militaristic recovery;

- The lifting of the arms embargo on the Somali government, as a testament to Somalia’s increasing security, the responsibility of the military to their arms, and Somalia’s decreasing dependence on African Union intervention forces;

- Somalia’s entry into the East African Community (EAC), as a testament to Somalia’s recovery of its political institutions, and their increasing stability;

- The overwhelming majority of Somalia’s debt being forgiven by the Paris Club, as a testament to their economic recovery;

- And significant gains in Somalia’s economy, such as sharp increases in Somalia’s GDP, and their debt compared to GDP percentage falling drastically in the span of just a few years.

All of these factors show progress in individual sectors of Somalia as a nation, and will be gone over in detail.

The Fight Against Al-Shabaab

The fight against Al-Shabaab, an Islamic militant group based in Somalia, has been a nearly 20-year-long battle. Beginning in 2006, Al-Shabaab’s militancy has fueled much of the civil war and increased civilian casualties, with urban attacks and bombings being consistent methods of control and influence for much of Al-Shabaab’s insurgency.

Al-Shabaab is responsible for the deadliest terror attack in Somalia’s history; the twin truck bombings that exploded in Mogadishu’s Hodan district, destroying a hotel and killing 500 people, while injuring 300 more.

While the fight is certainly far from over, the Somali government has managed to hold Al-Shabaab back with the assistance of African Union intervention forces, as well as air and intelligence support from the US.

In more recent years, the Somali military, with the backing of US air strikes, has managed to push Al-Shabaab back in a number of areas. A continuous effort, a significant amount of this progress has been after August of 2022, when President Hassan Sheik Mohamud declared a “total war” against the militants.

Al-Shabaab remains a significant threat and is a core factor behind the continuance of the civil war. However, Somalia’s notable gains against the group and improvements in its counterterrorism efforts have resulted in the African Union’s intervention force (African Transition Mission in Somalia, or ATMIS) slowly handing over security responsibility to Somalia’s military forces.

This force, ATMIS, is set to withdraw from Somalia by the end of 2024. So far this year ATMIS has already completed two phases of its withdrawal, removing several thousand troops from the country. Provided Somalia maintains its progress in this manner, the ATMIS withdrawal will continue.

Al-Shabaab still carries out attacks in the nation, including in Mogadishu, however not at the scale or with the frequency to which they used to.

Arms Embargo Lifted

Within the wider context of Somalia’s civil war, the UN Security Council had instituted an arms embargo against Somalia. The embargo, which was voted on and went into effect in 1992 (one year after the collapse of Barre’s government), prohibited the sale of arms to Somalia. At the time, Somalia did not have a central government, and so technically this ban only realistically applied to non-state actors, as there was no state actor. Upon the establishment of the Transitional National Government in 2000 and the Transitional Federal Government in 2004, the ban was applied to them.

Beyond just an arms embargo, in 2002 the UN further refined the embargo to include banning any financing for Somalia, or the militant groups within, to attempt to purchase arms themselves, as well as the sale or suppliance of any military training or technical advice.

Over time, certain restrictions were lifted, added, or existing ones extended. An embargo was also implemented on Eritrea in 2009, due to reports that Eritrea had violated the arms embargo and supplied equipment to armed groups in Somalia, as well as their refusal to withdraw from disputed territory with Djibouti. This embargo was lifted in 2018.

For Somalia, all restrictions on the suppliance of arms, and training, were lifted in December of 2023, though maintained upon non-state actors.

The lifting of the embargo followed a number of reports that Somalia had made significant gains in their “weapons and ammunition management capability,” reducing the chances that Somalia’s military equipment ends up in the hands of Al-Shabaab, or other militant groups and non-state actors in Somalia.

Furthermore, the end of the embargo comes within the wider context of gains made by the Somali government and military against Al-Shabaab. Within this context is the increasing self-reliance of Somalia for its own security as ATMIS withdraws from the nation, making it important that Somalia is able to be properly equipped for the job.

The East African Community

Somalia’s entry into the East African Community (EAC), a 12-year-long dream, finally came to fruition in March 2024, when the ceremony for Somalia’s accession to the EAC took place following its admission in 2023. Somalia, originally applying to the bloc in 2012, brings a number of different benefits to the EAC, just as the EAC brings a number of benefits to Somalia; immediately, in the short-term, and in the long-term.

When Somalia originally applied to join the EAC in 2012, they were not admitted due to their instability, both in the weakness of their political institutions and the risk posed by the Al-Shabaab insurgency. This insurgency locked down the Somalia-Kenya border, as Kenya, which continued to suffer several deadly attacks from Al-Shabaab, attempted to prevent a major cross-border spillover of Al-Shabaab. The insurgency’s access to the border further complicated the prospect of Somalia’s entry into the EAC.

As time has gone on, the intensity of Al-Shabaab’s insurgency, while still present, has decreased. At the same time, Somalia’s political institutions have marginally strengthened, as was proven by their ability to hold an election in 2022, though this election was not without problems.

In January of 2023, the EAC launched a verification mission in order to assess Somalia’s readiness to join the bloc. Several months later, in June, this mission finished, and negotiations for Somalia’s entry began.

The EAC’s heads of state accepted Somalia, making Somalia their 8th member. The other seven members are Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

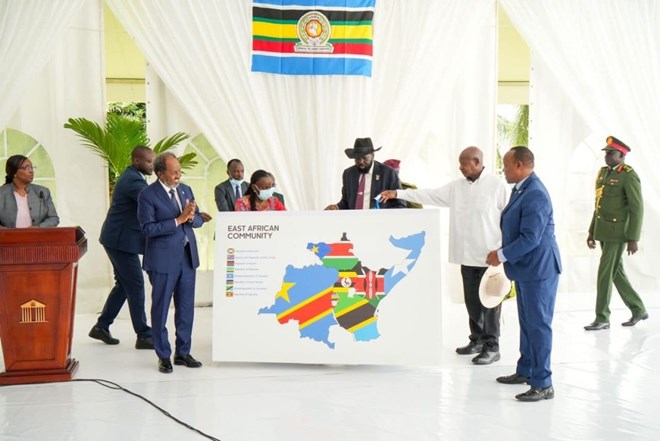

A photo of Somalia’s accession ceremony to the East African Community.

This grants Somalia a number of benefits. Firstly, it grants Somalia a strengthened political relationship with many other nations in East Africa, particularly Kenya, who is a key player in regional politics and economics.

Secondly, it grants Somalia increased trade, business, and education opportunities with the other nations in the bloc. Member states of the EAC are to have a unified customs union, as well as a common market. These two aspects promise a significant economic benefit for Somalia, however, remain to come into full force, partially because of Somalia’s newness to the bloc, but also because the Somalia-Kenya border remains closed.

In 2023, Somalia and Kenya announced their hopes to reopen the approximately 800-kilometer border. However more recently, in April, Kenya’s Interior Principal Secretary, Raymond Omollo, announced that the border would remain closed for the foreseeable future, citing the challenges of properly securing the border.

Secretary Omollo established no specific timeline for the opening of the border, only stating that “maybe after a few months to almost a year we will be able to make these border points [between Kenya and Somalia] fully functional,” with the timeline largely being dependent upon any security issues that may arise from the ATMIS withdrawal.

While Somalia has yielded some economic benefit from their entry, and increased trade relationships with several of the member states, the total potential of these benefits cannot be reached until this issue, too, is overcome.

Beyond the direct economic benefits, Somali students will also have more freedom to travel and study within the other nations of the EAC. Job immigration is also made significantly easier, representing a localized increase in opportunities for Somali workers.

Thirdly, this brings Somalia within the borders of what will become the East African Federation. While in its present form the EAC is largely a political and economic bloc, the EAC plans to eventually unite into one nation, known as the East African Federation. This is to take place in four stages. The first two stages, the customs union and the common market, have already been achieved.

The theoretical next step, a monetary union (a single currency), was supposed to be implemented in November of 2023. As this date came and passed, the EAC changed their target, with Pantaleo Kessy, the principal economist in charge of monetary affairs at the EAC secretariat, stating the EAC was “giving ourselves until 2031” due to delays amongst some member states for achieving the convergence criteria necessary to make the monetary union.

The last step, political federation, has the potential to turn the East African Federation into a developed nation in a matter of years following its establishment. However, the federation will face a number of hurdles in the way of doing so.

Somalia, as a member of the EAC, still has a number of changes to implement. Beyond the economic changes that will need to take place in order to ensure its integration into the bloc, Somalia also must begin to modify aspects of its legal system in order to make it akin to other member states. This is something that all members must do.

Besides the benefits it grants Somalia, Somalia’s entry into the EAC also grants significant benefits to the bloc. Namely, it gives the EAC access to the Horn of Africa, and thus the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Somalia being granted entry to the EAC after more than a decade of effort represents the gains in both political strength, as well as in reestablishing security in the nation, though both aspects continue to have room for growth.

A Debt Forgiven

In December of 2023, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank announced Somalia’s completion of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, further announcing Somalia’s qualification for up to $4.5 billion in debt forgiveness.

The HIPC is an initiative headed by the IMF and the World Bank to assist poor nations with achieving debt forgiveness from associated creditors, namely the IMF and the World Bank themselves, as well as the African Development Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the ‘Paris Club,’ a group of 22 different major creditor countries, including the entirety of the G7.

In order to qualify for this debt forgiveness, nations need to meet a series of criteria. The most important of these criteria is that the nation must enact a series of reforms: economically, legally, and within the business practices of the nation. These reforms are agreed upon between the applying nation and the IMF at what is called the “decision point,” which is when the IMF and World Bank allow the nation’s entry into the initiative.

For Somalia, this debt relief came recently. In mid-March, the Paris Club announced the relief of virtually all, 99 percent, of Somalia’s debt. In total, $2 billion in debt was forgiven.

A photo of Somalia’s Minister of Finance, Bihi Iman Egeh (Photo from BihiEgeh on twitter).

The relief of Somalia’s debt is likely to significantly increase the Somalian state’s ability to provide competent services for its people. According to the IMF, nations which benefitted from the HIPC spent an average of “five times more on health, education, and other social services than on debt service,” compared to before HIPC, when they spent “slightly more on debt service than on health and education combined.”

For the Somali government, increasing these services could help build legitimacy in the eyes of the Somali people, who have lived under a number of different leaders and governing forces in recent decades.

Somalia’s completion of the HIPC serves as evidence of Somalia’s economic gains, as it is the direct result of its years of reform in order to strengthen the economy. Somalia, of course, remains poor. However, the debt relief granted by the IMF, World Bank, and the Paris Club provides Somalia with significant potential for the future. Insecurity will remain one of the largest inhibitors for achieving this potential.

Somalia’s Economy, By The Numbers

The Somali economy has undergone a number of shocks in recent years. Like much of the world, the Somali economy shrank in 2020 as the economic effects of the Covid-19 pandemic became apparent worldwide. Other than in 2020, Somalia’s economy has expanded, making decent gains each year. In recent years the year-over-year growth has not been as substantial, however, Somalia’s economy has nearly doubled in GDP since 2013.

In 2013, Somalia’s GDP stood at $5.84 billion. By 2022, this had expanded to $10.42 billion. Somalia’s GDP per capita, while not increasing at the rate the GDP had been, has increased substantially as well. In 2013, Somalia’s GDP per capita stood at $454. By 2022, this had risen to $592.

Despite these gains, Somalia’s economy and wider stability trends face significant challenges. Floods and drought have significantly affected agricultural productivity, and rising food prices across the Horn of Africa exacerbated these issues, leaving many go without reliable sources of food and certain essential items.

As such, large portions of Somalia’s population remain in poverty, and millions are dependent or semi-dependent on aid assistance from organizations such as the UN.

Unemployment also remains an issue, with approximately 19.2 percent of Somalia’s labor force unemployed. Unemployment, particularly youth unemployment, is a large issue in many African nations, sometimes due to a “youth bulge.” People under 30 years old represent more than two-thirds of Somalia’s total population—one of the largest youth bulges in the world. As a result of more than 25 years of conflict, two generations of youth have lacked access to education and employment.

Job creation and poverty reduction will be two important tasks for the Somali government to undertake in the near future. While Somalia’s economy has made significant gains, many of the people have yet to see extensive benefit from these gains.

Regardless, Somalia’s statistical improvements are undeniable, and show their path towards economic recovery.

Growth Through Challenges

As mentioned, Somalia still faces a long road to prosperity. While its economy has made remarkable gains, they are fragile and prone to reversal. The opportunities presented in recent years to Somalia, namely their debt being forgiven and economic opportunity promised through their entrance into the EAC, will have to be properly capitalized upon in order for benefits to become a permanent part of Somalia’s future.

Furthermore, the strength of Somalia’s political institutions remains dependent on their ability to continue being the dominant force in the war against Al-Shabaab. While Somalia has been pushing Al-Shabaab back, until the insurgency is defeated there remains the possibility of a resurgent insurgency.

Besides these key issues, Somalia also faces unpredictable environmental and regional risks, such as drought (alongside much of East Africa), food insecurity, regional tension between Somalia and Ethiopia, and separatism from Somaliland in the north.

Despite all these challenges, some recent and some long-standing, Somalia has managed modest growth, demonstrating a resilient nation heading into the future.