Friday February 9, 2024

East London's Bethnal Green is where you will find the fighter looming larger than life out of a community mural three storeys tall

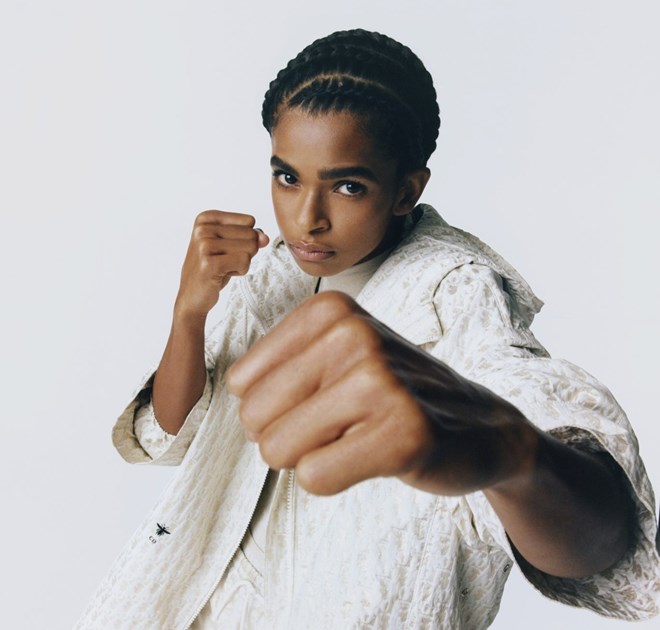

Because of a gender pay gap in prize purses offered in boxing, professional super-bantamweight Ramla Ali, above dressed by Christian Dior, is forced to rely on the substantially more lucrative side hustle of modelling. Photo: Ramla Ali

Soon after the bell sounded to end Ramla Ali’s second professional fight, the Somali-born boxer was in a room behind the ring at the SSE Arena in Wembley crying dejectedly.

The tears were not because she lost. She didn’t. Nor were they because a doctor was stitching a nasty cut – her first ever – that opened up in the fifth round above her left eye.

“I was crying because I thought my face was not going to look the same ever again,” Ali tells The National. "Nothing to do with the pain. I was thinking: ‘I’m never going to get modelling work now. It’s my only form of income. How am I going to continue boxing?’"

In that almost faultless performance, she proved her trainer’s mantra that “you can’t beat the feet’’, lightly feinting and triggering, while leading with a deft left jab.

If the stance marked her as orthodox in the ring, life beyond the ropes has been anything but.

Three decades after she claimed asylum in London as a toddler with her family, guest editor Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex, chose Ali to grace the cover of the September 2019 British Vogue issue as a “Force for Change’’.

She turned up to the photoshoot a bundle of nerves and bearing one of the occupational hazards of the day job.

“I had a black eye but you can’t see it," she says. "That’s why I’m the only one who’s sideways.

"I’ve realised that the fashion world isn’t really how people think it is. It’s not superficial, it’s amazing. They understand who I am and they celebrate it. Now, looking back on why I was crying, I feel silly knowing how much they embrace differences.”

Middle East dreams

Inclusion is important to Ali. She devotes considerable amounts of time to being an equal opportunities activist and working as a humanitarian with the aid organisation Unicef.

Perhaps her greatest labour of love is Sisters Club, the non-profit initiative founded in 2018 to give women of ethnic and religious minorities and victims of violence a safe place to box.

It is not a case of just doing exercises and then whacking a bag, she clarifies. “It is self-defence. The free weekly sessions teach vulnerable women and girls to move like a boxer and protect themselves against punches."

Clubs in London, Los Angeles, New York and Texas offer the Sisters various sports from boxing and basketball to running, football and rowing, and Ali, currently in Dubai for the launch of the SIRO One Za'abeel fitness hotel as a brand ambassador, hopes to expand into the Middle East.

A taster event was held for 40 female participants wanting to try boxing at a media workout in Saudi Arabia before the historic fight against Crystal Garcia Nova 18 months ago. “This is the whole point,” she says.

The super-bantamweight bout on the undercard of the Oleksander Usyk v Anthony Joshua rematch ranks high in her favourites because of “how I won it” (knockout right punch after 65 seconds), “where it was” (Jeddah), “what it meant” (the first time two women had fought professionally in the kingdom), and the “celebration” (a drive to Makkah to perform Umrah).

Ali knows all too well the strength it takes to defy convention, rewrite the rules, push through obstacles, or embrace being different.

In childhood, she routinely lied about her ethnicity, inventing any alternative birthplace to better blend into the mainly Asian population where she grew up.

Then came more than a decade of hiding bruises from a disapproving family, sneaking out the window for sparring sessions, and pretending to be elsewhere while going off to compete.

She also struggled with imposter syndrome, feeling like an outsider taking up space to which she had no right on the canvas and later in front of the camera.

'You’ve gotta beloud-er'

For the Met Gala 2022, Ramla Ali wore a white ruffled and feathered Giambattista Valli haute couture tulle gown. Getty Images

These days she has her eyes on the prize of closing the gender pay gap in boxing, and urges fans to help by supporting female pugilists.

Things are moving in the right direction as Ali found during her points win against Agustina Rojas at the O2 Arena in July 2022 when coach Manny Robles couldn't understand why his instructions were being ignored.

Sisters Club had rallied, many from the local Somali community came in spite of it being a religious holiday, and her family was there as well.

Fellow IMG model Sabrina Dhowre Elba was in the crowd along with Jamaican-British actor Michael Ward, Fast & Furious film franchise producer Vincent Samantha, British Vogue editor Edward Enninful, Cartier managing director Laurent Feniou, and even Ilhan Omar, the Somalian refugee and US Congresswoman representing Minnesota, flew in.

“It was incredible," Ali says. "I couldn’t hear my coach. I said to him: ‘You’ve gotta be loud-er.’ So that was nice.

“I’ve shown the promoter Matchroom time and again that I bring a different sort of clientele to watch. And isn’t that what sport is all about?”

Her autobiography, Not Without a Fight, detailing 10 of Ali's pivotal challenges, is dedicated to anyone who has ever had the same feeling of not belonging. “You’re not meant to fit in,” she says. “You’re meant to stand out and be great.’’

A forthcoming Film4 biopic will be directed by Anthony Wonke, and it seems almost too good to be true that Letitia Wright, who starred as Black Panther in Wakanda Forever, has been cast as the lead.

Panthers, two of which are on the Somali coat of arms, have been synonymous with Ali’s career, and menacingly adorn her custom-made designer satin robes and shorts.

“Letitia is the perfect person for the role. We have similar personalities.

"The fact she wants to get to know my family," she says, producing a photo of the actress with her relatives at Eid, "shows she wants to do the part justice. That’s the type of person you want telling your life.”

When we meet, it’s in a trendy hotel in Shoreditch near her old stomping ground, and Ali is with husband Richard Moore between their gruelling morning and afternoon training sessions that continue even when the couple are fasting during Ramadan.

Not that far away, where Bethnal Green Road and Barnet Grove meet, her face looms larger than life out of a community mural three storeys tall, the born fighter gazing watchfully over all those below.

Inseparable couple taking on all opponents

Moore, who converted to Islam eight years ago, is content with being known as her “professional bag carrier” but he has been Ali's motivator-in-chief, manager and arguably most important coach.

The two met at a boxing club in south London when Moore was on a visit back from making documentaries in the US in June 2016. Their eyes met across the sweaty gym. He fell hard. She not so much.

But the great-great-grandson of a bare-knuckle fighter, great-grandson of a professional middleweight, and grandson of England football coach and former boxer Dave Sexton wasn’t giving up that easily.

Having said his shahada in a mosque in Peckham, he soon proposed and they married in a Nikah ceremony four months later.

An inseparable unit, they travelled the world taking on all opponents inside and outside the ring to help found the Somali Boxing Federation for a country where the sport had been banned since 1978.

It was a long, expensive and ultimately personal journey for Ali to proudly reclaim as a young woman the family heritage that she had found so irksome as a girl.

She is wearing a top bearing her likeness and the words “Made in Mogadishu”, although no one knows exactly when, other than near the start of the civil war.

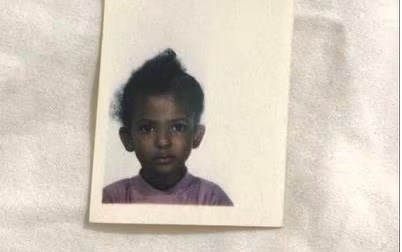

With no birth certificate to consult, her eldest sister Faiza chose September 16, 1989, which puts Ali at 34-ish.

Stories of her early years in east London were handed down, but how they all got there wasn't revealed until Moore sought some background about his bride from her mother, through an interpreter.

Ali was to discover that she had had an older brother, Abdulkadir, 12, whose fatal wounding from a stray grenade while playing outside the family home set in motion a sequence of events that shaped her life.

There was the journey by van to the Somali port city of Kismayo; a month of living on the floor of a coal yard; somehow borrowing money for the sea passage after their possessions were stolen; the overcrowded boat to Mombassa on which many lost their lives; and the year her mother regularly queued hours for essentials from aid organisations while her father worked in construction to pay for flights to the UK on fake Kenyan passports.

Racism and bullying in early years

It might seem hard to understand why Ali had gone so long without having these crucial missing pieces that put together the puzzle of her past but, as she explains, many African households don’t talk about their feelings.

“A lot of people let their experiences sort of dictate their lives, how they behave and their personalities. My mum is not like that. She just gets on with it. She was so strong for us. She’s the best fighter I know.”

After landing at Heathrow in 1992, the six siblings and their parents were taken to refugee accommodation in Paddington before living in a series of flats and finally settling in a council house in Bethnal Green.

Some constants throughout the moves were the strong smells of Somalian cooking from their kitchen permeating their clothing, the plastic coverings that would be whipped off to reveal pristine sofas and rugs for guests, and the excuses that an embarrassed Ramla concocted to avoid inviting anyone over herself.

She experienced racism and bullying, and sought sanctuary in books, finding a particular kinship with Elizabeth Bennet in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

When a doctor warned that the 14-year-old was becoming obese, her mother paid for a junior gym membership at a leisure centre and everything changed.

Peering through the window of a boxercise class, she was intrigued but too afraid to go in on account of not seeing anyone who even vaguely resembled her.

On managing to enter in a second attempt a week later, Ramla took the initial faltering steps towards winning English, Great Britain and African Zone titles, and becoming the first fighter to represent Somalia at an Olympics.

Praying for a safe fight

“A lot of people from the outside probably see my career as just straight," she says. "You’re at the bottom and then you’re at the top. They don’t realise that there are loops and turns and ups and downs to get there.”

Parental expectations of a degree compelled Ali to attain a first in law at SOAS, University of London, even as she continued to pursue her boxing passion. Along the way, misogyny, the lack of representation, injuries and financial difficulties also impeded her sporting progress but trickiest of all was the secrecy she had to maintain to avoid intervention.

Women exchanging punches in the face for a living didn’t align with her mother’s interpretation of the Muslim faith. Nor did her parents go to such extreme lengths to remove Ali from a war zone, only for her to then deliberately put herself in harm’s way.

The sport is dangerous, concedes Ali. “Most people don’t die in boxing, obviously, but most do leave with serious injuries – CTE [chronic traumatic encephalopathy], issues with their arms.

“I try to negate that. I do hyperbaric oxygen therapy even if I’m not in camp. It’s all about reducing inflammation. Suddenly, you’re mindful not just of performance but life after boxing.”

A group of Tower Hamlets young people inspired by local hero, international boxer Ramla Ali, launch a new permanent mural.

She has no fear of being hurt but never steps through the ropes for a match without praying for self-belief and a safe fight. Never for a win, despite the fact that what she is most afraid of is losing.

Over the years, she has learnt to let go of pride and make peace with the bad days that are, Ali says, just bad days – even the one last June in New Orleans when a sudden left hook from Julissa Guzman inflicted her only defeat in nine fights as a professional.

“That’s boxing. I was heartbroken for about 24 hours. I know I was winning based on the judge’s scorecard. It was just a really good shot.

“But you can’t let one loss define your entire career. I always come to the conclusion that we love to plan things for ourselves but God plans things for us as well – and he’s a better planner than we are.”

Nonetheless, Ali surprised many by immediately seeking a rematch, and won by unanimous decision five months later in November in Monte Carlo. Having righted what she saw as a wrong “for my own sanity, basically”, she can now carry on.

Proud mother won over

The ambition is still to win a world championship as is continuing the work that saw Ali recognised by Time magazine last year as one of 12 extraordinary leaders fighting for a more equal world.

Eventually, through persuasion from Moore and an uncle in Somalia, her mother has come around, particularly for the many efforts to give back to community and country.

“She’s proud that I remember where I came from. But she would still rather that I just start a family," Ali says, rolling her eyes.