By ABDULKADIR KHALIF

Sunday April 7, 2024

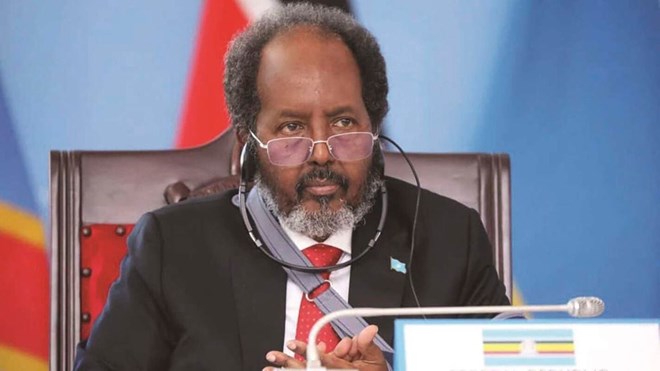

Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. PHOTO | POOL

Somalia has, since the start of February, been trying to rewrite the Constitution, redirecting focus on a document that could encompass the basic principles and laws and determine the powers and duties of the government and its citizens.

It is an exercise that should have been done years ago but was delayed by fragile state institutions and the general security problem posed by the Al Shabaab.

On Saturday, the bicameral parliament passed certain amendments to several articles in the first four chapters of the provisional constitution of 2012.

But the move caused more cracks by smoothing over past divisions. Puntland, the semi-autonomous federal state and one of the oldest in the country, promptly rejected the reviewed constitution stating, “the constitutional amendments are a violation of the federal pact that historically unified the country.”

Puntland President Said Abdullahi Deni followed this with a decision to ‘suspend’ membership its in the Federal government, where four other federal states exist: Jubbaland, South West, Galmudug and Hirshabelle.

Omar Abdirashid Sharmarke, another former Prime Minister, and Abdirahman Abdishakur, a legislator, endorsed similar views to Hassan Ali Khayre, a former Prime Minister, rejecting the proposed review.

Somalia’s political actors are at loss as to choose either multiparty democracy or 3-party system as well as the powers the executive arm of government should have.

President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud promptly signed into formal law the parts the bicameral parliament amended on March 30 modifying the type of political system the country will play.

It changed to a presidential system whereby the President of the Republic is elected by popular vote with the faculty to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister.

Currently, the President is elected indirectly by legislators voted in through a type of college system, based on clans. The new system will mean the Prime Minister will no longer need parliamentary approval and will have little powers in running government affairs. Today, the Prime Minister appoints and fires ministers and runs the government, answerable to the federal parliament.

The changes are being challenged by former Somalis presidents, former prime ministers, legislators and Puntland State who oppose the review process, underlining lack of consensus.

The original version of the constitution in use in Somalia was framed when Somalia adopted a federal government from the Somali Republic at the end of the Somali Reconciliation Conference at Mbagathi in Nairobi, Kenya, from early 2000s until it was adopted formally in 2012.

At the time, delegates seeking to rebuild Somalia from the civil war approved a multiparty democracy and a parliamentary system of government. They first wrote the Transitional Federal Charter in February 2004 that was finally endorsed as a Provisional Constitution in August 2012 in Mogadishu, Somalia.

On the governing system, the provisional constitution was not much different from the constitution of Somalia’s first civilian republic in the 1960s.

“Unlike the rest of Africa, Somalia had adopted the parliamentary system of government, meaning that the president of the Republic is elected by the parliament, not by the people, for the duration of six years,” Mohamed Issa Turunji, a Somali researcher, wrote in the book: President Aden Abdulla, His Life & Legacy, about the life and legacy of Somalia’s first post-independence president.

“By virtue of this system, the executive power was vested not in the President of the Republic but in the government led by the Prime Minister. The president had the role of representing national unity and guaranteeing that politics complied with the constitution.”

Somali politicians often speak of the ‘stages’ of their republic. The “First Republic” was formed in July 1960at independence, governed via a multiparty democracy and a parliamentary system. Its constitution was abolished when the military took power via a coup in 1969.

The military rulers introduced a pseudo-socialist constitution with one-party rule and a popular elective system where the President could appoint and fire a Prime Minister.

The stage lasted for two decades (1969-1990) and was labelled as the “Second Republic”.

When rebel groups defeated the military dictatorship of Siad Barre in 1991, followed by years of chaos, the rebirth of the republic came through a series of reconciliation conferences, the last being the one concluded at Mbagathi, Nairobi. The Somali politicians named the rebirth as the “Third Republic.”

Those who want and promote a parliamentary system base their argument that it is easy and more democratic. Abdirahman Abdishakur, an MP and former presidential candidate in 2022 elections, explained that electing the legislators by a popular vote is feasible, and said the MP and Senators electing the president is more controllable process.

“Let us leave the one-person, one-vote to handle the parliamentarians,” Abdishakur argued, referring to universal suffrage which has eluded Somalia since 1969.

He argued that that three-round voting system by a known number of legislators cannot yield mistakes.

“For the past two decades in state building the parliaments elected presidents six times through casting ballots in crystal-clear glass boxes,” he added, questioning, “Who had seen a president-elected being criticised for rigging?”

So, what next?

First, on the argument over governance system, some opponents of the presidential system say the government forming process in the “First Republic,” when the parliament had the power, meant the President could not overstep.

They argue that the President of the Republic could appoint the prime minister and parliament could veto it with a vote of no confidence.

That process was not cumbersome because the president would have no problem in picking a prime minister, belonging to the political party (or a coalition) commanding the majority of parliament.

For Somalia though, a new system, just as in the existing system, provides existential challenges. There are no political parties and most political games are run on clan-based influences. Recently, the presidents have appointed Premiers with no political track-records. In some instances, such as during the tenure of Mohamed Farmaajo, a president and premier bickered in public, indicating a broken executive.

Some have argued a prime minister needs political skill too as, whenever there is problem, the president and the premier have equal opportunity to advocate their policies and lobby to the legislators.