Sunday May 6, 2018

'I wanted to show the beautiful and amazing and resilient people that we are'

By Shanifa Nasser

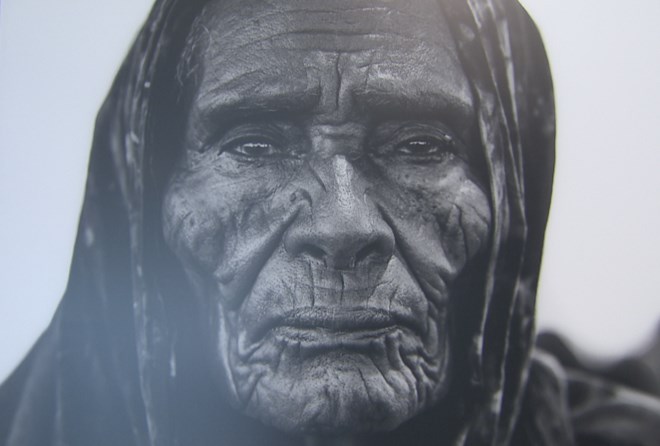

Yasin Osman is the photographer behind “Dear Ayeeyo," an exhibit he describes as a love-letter to his grandmother, which opened Friday at the Daniels Spectrum auditorium as part of the Contact Photography Festival. (CBC)

A thousand little lines etched onto her face quietly tell a story of struggle and resilience, of dreams fulfilled and not — of a life not to be forgotten.

In the eyes of a woman he met halfway around the world in Somalia, Canadian artist Yasin Osman saw his own grandmother.

Only it wasn't. Osman's own ayeeyo (grandmother) had just passed, her words echoing in his mind, inspiring him to use his photography to show a part of Somalia most of the world had never seen or bothered to see.

"Remember me," the woman told him as they parted.

A chance to shine a light

Just months earlier, Osman was sitting with his grandmother in the United Kingdom where she lived during their first visit together in nearly a decade. They spoke of the future, Osman weighing leaving his job as an early childhood educator to pursue photography full time.

His grandmother motioned to the television screen, where a Somali journalist was telling a positive story about her home country.

"I will pray for you," Osman's grandmother told him, on one condition. She would support his career choice if he promised to use his gift of photography to do good for Somalia.

It was to be one of their final conversations.

Traveling to Somalia wasn't in Osman's immediate plans. But when he returned to Toronto following his grandmother's death, he quit his job and set about looking for ways to fulfil his promise.

It wasn't long before he came across the an online famine relief campaign a called Love Army for Somalia and started messaging back and forth with Jerome Jarre, one of the social media celebrities involved, sending samples of his work. Jarre, remembers Osman, was immediately drawn to his work, and invited him to come to Somalia to help document the effects of the drought.

It was a chance to shine a light on stories of Somalis that rarely made headlines.

Shoot For Peace

An only child raised by a single mother in Toronto's Regent Park neighbourhood, Osman knew all too well the dark shadow cast by negative stereotypes, teasing about Somalis being pirates, the assumptions that his was a community infiltrated by gangs.

"When I grew up, there was a lot of gun violence in Regent Park and so how I wanted to tackle that issue was by using my gift — I believe every single person in this world has a gift — and I wanted to share my gift by teaching young kids about photography."

That desire is what sparked Shoot For Peace, a weekly program for children in Osman's childhood neighbourhood to learn to express themselves through the art of photography. Every Sunday beginning in the fall of 2015, Osman would get together with a group of kids, letting them take snaps of things and people that mattered to them.

"It didn't cost us money to just walk around the neighbourhood with a camera... And it was amazing because the kids were slowly opening up."

But it was when one of the young boys came up to Osman and said he didn't realize he could do anything besides what he'd learned in school, that he might want to become a photographer, that Osman realized how powerful the program could really be.

"Just for him to have that choice, that option of doing something other than what he knew about... It made me really feel like I did the right thing."

'We are all your brothers'

Fast forward to 2017, Osman found himself on a flight to Mogadishu for his very first visit to Somalia to in his own way to put a human face to a country so much of the world associated with crisis.

"I remember being on the plane and it was a really emotional flight for me because I remember thinking how happy my grandmother would have been if she knew that I fulfilled my promise of going back," he said.

The Somalia he saw was nothing like the stereotypes he'd heard growing up — there were engineers, doctors, teachers, mothers, elders, children, ordinary people that looked like Osman and were working to support their communities.

"When I first got out of the plane and I went into one of the vehicles, the man asked me, 'How many siblings do you have back in Toronto?'"

"I don't have any siblings," Osman remembers replying. "Then he grabbed my hand and he said, 'Stop, don't say that, I am your brother and we are all your brothers.' That really touched me."

"That's what I wanted to show... I wanted to show the beautiful and amazing and resilient people that we are because a lot of times that's not what's translated into the media."

Then there was Amir, about six or seven years old. Osman had brought along some treats for the kids and Amir was handing them out to his friends, so Osman said to him, "Why don't you take some to keep for yourself?"

"And he said to me, 'Why would I keep them for myself when we don't know if tomorrow's coming?'"

And of course there was the ayeeyo who looked so much like his own — a reminder of who and what all this was for.

"So creating this exhibit and making this a tribute to her... this was kind of like a love-letter to her, to say, 'I did what you told me. And I hope you're proud of me.'"

With files from Dwight Drummond, Metro Morning