Tuesday December 19, 2017

There is a marked contrast between what 60% of South Africans believe about migrant entrepreneurs from Somalia, Nigeria and Senegal who live in Cape Town and actual findings confirmed by research.

A survey in 2010 found that the majority of South Africans believed that one of the reasons for the xenophobic violence in 2008 was that migrants were taking jobs from South Africans, that they were engaging in illegal and other nefarious business practices and driving local small businesses to the wall.

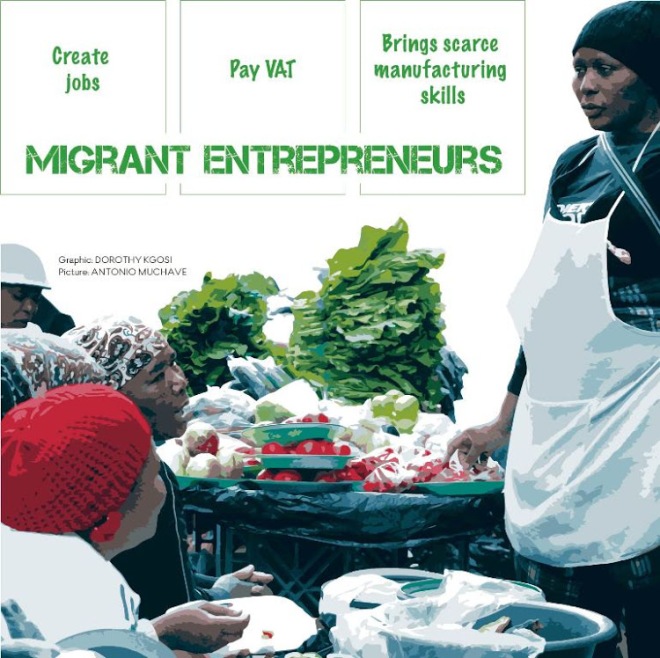

However, a study of migrant entrepreneurs from these countries — and confirmed in the Southern African Migration Programme survey conducted in Johannesburg and Cape Town — found that, contrary to these beliefs, migrant entrepreneurs create jobs for other migrants and South Africans, slightly favouring the employment of South Africans.

Other findings were that migrant entrepreneurs also make other contributions to SA’s economy.

All evidence points to the fact that migrant businesses source their goods in the formal economy and contribute to the tax base by paying value-added tax. They have also introduced a diverse range of products, business activities and opportunities and brought scarce manufacturing skills into the township economy.

Key beneficiaries are poorer consumers who can access cheap goods, often in appropriate quantities and at convenient times of day and locations. The migrant entrepreneurs’ competitive edge stems from careful attention to product sourcing and servicing customer needs — their business model is based on low mark-ups and high turnover, making a greater variety of goods available in flexible quantities, a culture of thrift and the long hours they are prepared to work.

Under any other circumstances, they would probably be praised as shining examples of micro-entrepreneurship. But the government and many citizens view their activities as undesirable solely because of their national origins and the ease with which they can be scapegoated as the cause of unrelated political and economic issues.

Harassment, extortion and the bribery of officials are among the daily costs of doing business for migrants in SA. Many entrepreneurs, especially in informal settlements and townships, face constant threats to their security and minimal protection from the police — in addition to the constraints they face simply because they operate informally.

In SA, the informal economy has at best been ignored and at worst actively discouraged. The antimigrant sentiment is driving a process of severe regulation that will further endanger the livelihoods of migrant entrepreneurs.

In the past decade, there has been a retrogression in the policy environment relating to migrant entrepreneurs, asylum seekers and refugees. SA’s migration and refugee policy has shifted away from the former integrationist approach to one of containment and repulsion.

This is most evident in the 2016 Refugees Amendment Act, the recent green paper on International Migration in SA and the current construction of what the Department of Home Affairs has termed "a processing centre" near Messina, Limpopo. Only 10% of international migrants who have applied for asylum or refugee status have been granted this status.

The government believes only 10% of the applicants are asylum or refugee status seekers — the rest are economic migrants. This remains their argument despite the consensus among experts and researchers that the percentage of actual refugees and asylum seekers is considerably higher than 10% and that migrants have a positive effect on national economies.

According to the 2015 white paper, there were 78,339 active asylum-seeker permits. Public education initiatives to educate South African citizens on issues of xenophobia have not had any measurable effect, due largely to legislation, policy and attitudes in the government becoming increasingly unwelcoming of migrants and the seemingly intractable xenophobic attitude of about 60% of South Africans.

Legal challenges to government departments, municipalities and metros have had far more success because of the tenets of the Constitution and the inclusive and comprehensive rights it assures to any persons residing in SA — both citizen and noncitizen alike.

One of the greatest challenges for migrants in SA is maintaining their self-reliance and assuring their right to work within the informal sector. Social protection of vulnerable migrant communities in SA needs to focus on protecting migrant-owned small, medium and micro-enterprises in the informal sector. These businesses are the migrants’ main source of income security and if their livelihoods are to be sustainably protected and community resilience maintained, their rights in this area are vital.

It is possible the legal challenges could set an important precedent in favour of these communities and form a key part of a sustainable solution to the problem of ensuring their social, legal and economic protection.

The government’s argument is that its change of approach has been driven by the overwhelming number of international migrants home affairs has had to process. The deleterious effects this influx can have on the national economy and SA’s social cohesion are simply not borne out by the facts.

In contrast, the facts lead to an understanding that the services provided by migrant entrepreneurs to poorer households in the townships (credit, smaller product quantities and a greater variety of goods) play a key role in food security strategies for these households.

Rather than the negative effect the government argues international migrants have, we see that on aggregate their businesses benefit the most vulnerable in SA and the economy. Do we need to ask who else would provide these services, if not migrants?

The migrant entrepreneurs are also among the most dedicated and resourceful entrepreneurs in SA’s informal economy. There needs to be an acceptance by the government and the public that neither the informal economy nor the migrants will go away.

Both are indispensable because they fulfil vital needs and services to the poorest of the poor. They are quite simply filling a gap in the market, and their businesses should be, at the least, left alone and, at the most, supported by the government and citizens.

Bax, formerly with the UN in Africa, is now director of NGO Resilience Africa. Capon is a resilience researcher specialising in security, conflict and development in sub-Saharan Africa.