Wednesday December 11, 2024

Few countries are more exposed to the ill effects of climate change than Somalia. Insecurity compounds the problem, with the Al-Shabaab insurgency exploiting drought conditions as a means of social control. Mogadishu needs help in dealing with the nexus of armed conflict and weather shocks.

What’s new? Somalia went through a prolonged, extreme drought between 2020 and 2023 that caused a humanitarian emergency and fuelled conflict with the Islamist militant group Al-Shabaab. Local resentment of the group’s harsh methods during severe water shortages eventually led to a military offensive that put the insurgents on the back foot.

Why does it matter? In Somalia, climate change and conflict are increasingly intertwined. Al-Shabaab uses access to water and other natural resources to levy taxes and fees on herders and farmers, as well as to punish communities that resist its control. But it has also proven persuadable by social pressure during climate shocks.

What should be done? Somalia urgently needs to build infrastructure to withstand future extreme weather more effectively. While funds are trickling in, Mogadishu needs help with adaptation measures. Given the country’s immense needs, the government should consider making climate resilience a central part of its efforts to engage Al-Shabaab in talks.

Executive Summary

Somalia is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change in the world. Serious weather shocks are hitting more often, harming livelihoods and economic growth. The 2020-2023 drought and later flooding highlighted the plight of millions of Somalis who rely on seasonal rains to grow crops or raise cattle. In the years to come, Somalis will continue to battle rising temperatures, erratic precipitation and biodiversity loss linked to climate change and deforestation.

Neither drought nor climate change created Al-Shabaab or caused Somalia’s instability, but both are now reshaping the conflict. From its origins as the enforcement wing of the Islamic Courts Union, a group of clerics who brought relative order to much of south-central Somalia after the central state collapsed in 1991, Al-Shabaab has positioned itself as an insurgency and the de facto governing authority in areas under its control. Over the years, overstretched Somali and partner forces have hunkered down in urban locales, while Al-Shabaab has established firm footholds in rural areas, above all in the south and centre of the country, where it has staged attacks on African Union forces, Somali troops and public officials.

As these rural areas succumb to the effects of climate change, Al-Shabaab has sought to capitalise on droughts by using access to water as a means of putting pressure on local people. But recent events have shown that this strategy can backfire. Frustration with Al-Shabaab’s demands for money and recruits, as well as its violent collective punishment for non-compliance during the drought, fuelled an uprising by clan militias, with which the Somali federal government allied to launch an offensive in August 2022. A number of desperate residents fled areas under Al-Shabaab’s control, bringing the group into discredit, causing its revenues to fall and heightening its exposure to attack from land and air. In response to the uprising, Al-Shabaab has made half-hearted efforts to deal with the harmful effects of climate change, on occasion building water infrastructure in a bid to curb local discontent. It has also taken rudimentary measures to protect the environment, like digging irrigation canals and reservoirs, banning logging and planting trees.

Despite initial gains, the offensive has been disappointing. The federal government is struggling to persuade locals in areas recaptured from Al-Shabaab that it can serve them better. With the help of international partners, it will have to step up local service delivery and look for ways to curb Al-Shabaab attacks, especially those on supply routes for humanitarian aid.

Mogadishu should do more to build resilience to extreme weather throughout the country.

While it does so, Mogadishu should do more to build resilience to extreme weather throughout the country. Somalia sorely needs adaptation measures such as sand dams, solar-powered irrigation and flood defences to reduce its climate vulnerability and improve the lives of its people, whose incomes mostly rely on agriculture or pastoralism. Ensuring that aid, basic services and support for climate adaptation measures reaches all Somalis amid conflict is no easy matter. But the government has signalled its interest in building climate resilience, and initial funding has been secured. In October, the Green Climate Fund approved a $95 million project for Somalia that, among other things, aims to revitalise degraded land and rebuild water infrastructure. It will also allow the Somali government to show prospective donors that its efforts to cope with future weather shocks are serious. Its reputation may well be on the line. Ranked among the world’s most corrupt countries, Somalia is dogged by perceptions of widespread graft.

Getting investment into areas controlled by Al-Shabaab will pose some of the hardest dilemmas. In those parts of Somalia likely to remain under the militants’ rule for the time being, the government should allow community leaders to engage with Al-Shabaab before and after extreme weather events or, at the very least, refrain from interfering with them. At present, elders may face arrest for meeting or signing agreements with Al-Shabaab. Even so, some Somali communities have negotiated access to water or pressed militants into lifting blockades, with local NGOs or private contractors stepping in to provide essential services. Without a doubt, there are dangers in local dialogue with Al-Shabaab, which has repeatedly destroyed basic infrastructure and provides no guarantees that it will honour any agreement. But even if negotiations under these conditions are far from ideal, they may nevertheless be one of the few options communities have for securing aid and preparing for future climate shocks.

Should the government choose to engage with Al-Shabaab in the future, the sides might also find common ground in attempts to alleviate climate stresses. By putting the emphasis squarely on delivering vital services like water, even in areas controlled by Al-Shabaab, the government could show that its priority is meeting Somali citizens’ needs. It could build trust with militants and pave the way for including climate policies on the agenda of dialogue seeking an end to the conflict.

If the sides agree to a political settlement, or even if Mogadishu weakens Al-Shabaab to the point of irrelevance, the problem of climate change will persist. Fresh emergencies could arise that other non-state armed groups may seek to exploit. Fighting climate change in Somalia is fraught with challenges stemming from conflict, disputed territorial control, scarce resources and corruption. Addressing the Somali people’s needs in the face of an often cruel climate will not only alleviate hardship but also weaken the sway of Al-Shabaab or other threats to the state.

Nairobi/Brussels, 10 December 2024

I.Introduction

Somalia now ranks sixth among the world’s countries in vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change, after Guinea-Bissau, Micronesia, Niger, the Solomon Islands and Chad. Weak governance and widespread insecurity compound the problem.1 From late 2020 onward, an historic drought in the Horn of Africa caused huge distress among Somalia’s population. Parts of the country’s southern and central regions saw almost three consecutive years of poor rains between late 2020 and 2023.2 Though rainfall gradually improved, floods in November 2023 displaced more than half a million people.3 It will take the country years to recover from these weather shocks.4

The drought and floods also put the Islamist militant group Al-Shabaab, which has been battling the authorities in Somalia for nearly eighteen years, on the back foot. The group, whose name means “the youth” in Arabic, first emerged as the armed wing of the Islamic Courts Union, a group of clerics who sought to stabilise the country after the central government collapsed in 1991. In the wake of Ethiopia’s 2006 military incursion to topple the Union, Al-Shabaab mounted a campaign of resistance that included high-profile bombings in public places and attacks on officials and journalists. The group later developed links to the transnational jihadist organisation al-Qaeda.

Soaring over the Jubba River in Somalia. 11 September 2022. CRISIS GROUP / Nazanine Moshiri

Despite a costly African Union-led intervention force and sustained donor support for a federal government that was re-established in 2012, Al-Shabaab continues to hold extensive areas in southern and central Somalia, even if its influence has ebbed and flowed over the years. Determined to strengthen its grip on communities in areas it controls, Al-Shabaab has sought to capitalise on the drought by using access to water as a means of coercing local people into doing its bidding.

This report assesses the ill effects of climate change in Somalia against the backdrop of the war with Al-Shabaab. It outlines Al-Shabaab’s responses to extreme weather crises, including the drought that ended in late 2023, and looks at how Al-Shabaab has used access to water to put pressure on residents of areas it controls. It also examines how the militants have changed their attitudes to building water infrastructure. The report builds on previous Crisis Group publications focusing on Al-Shabaab’s response to drought, the government’s offensive against the militants and the possibility of negotiating with the insurgency.5 It also draws upon more than 150 interviews with residents of southern and central Somalia, current and former Somali officials, employees of the UN and other international bodies, NGO representatives, researchers, journalists and academics. Interviewees included people who had fled Al-Shabaab-controlled areas. Around one third of the interviewees were women.

In addition to quantitative analysis that Crisis Group has produced itself, the report incorporates data from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on vegetation density, as well as other data from the Climate Hazards Center at the University of California-Santa Barbara and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

II.Somalia’s Climate Challenges

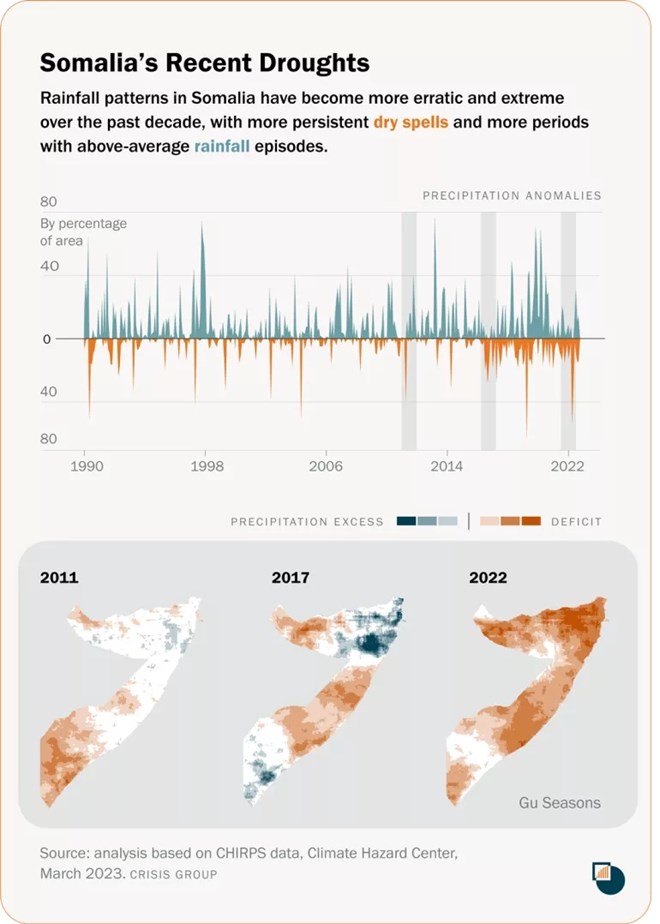

Somalia is vulnerable to weather extremes, which are increasingly undermining the livelihoods of farmers and herders. Rainfall patterns in the Horn of Africa, including Somalia, have become more erratic over the past decade. The country has been going through more dry spells (in Figure 1 below, note the rising number of orange areas) as well as more periods with above-average rains (the blue areas).6 Parts of Somalia experienced six consecutive below-average rainy seasons over three years between late 2020 and mid-2023. In 2019 and 2020, abnormally heavy rainfall led to flash floods in other places. Especially since 2020, these weather shocks have reduced agricultural productivity in parts of the country.7 Desert encroached on farmland due to the scant precipitation. Then, combined with strong winds, the sudden floods created ideal conditions for locust infestations that destroyed more than 200,000 hectares of crop fields and pastures in Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia.8

Sign of distress: a dead goat, a stark symbol of the drought in Somalia, lies on the road near Dollow, Somalia. 9 September 2022. CRISIS GROUP / Nazanine Moshiri

Changing weather patterns magnified the severity of the 2020-2023 drought are intensifying floods, too. Scientists say climate change made this drought 100 more likely than usual.9 What made the drought exceptional was not just below-average rainfall but also higher temperatures that scorched parts of the country, particularly at the beginning of 2022 and 2023.10 Although dry spells are common in Somalia, the 2022 April-June rainy season, known as the Gu, was among the driest on record.11 In 2023, the drought’s consequences endured, though it eased.12 In 2024, the Gu rainy season brought heavier than usual rains and floods, displacing thousands of people in thirteen affected districts.13

Figure 1

Flash floods are also becoming more frequent across the Horn of Africa.14 Heavy rainfall in the Ethiopian highlands, and occasionally in Somalia, swells the Juba and Shabelle rivers, especially during the Gu (which means “spring” in Somali) and Deyr (which means “autumn”), the country’s two main seasonal rainfall periods, which occur from April to June and October to December, respectively.15 From late March to April 2023, downpours in Ethiopia flooded Juba and Shabelle, displacing around 100,000 people in Somalia; the UN described it as a once-in-a-century event.16 The following May, severe flooding uprooted more than 200,000 people nationwide.17

Deforestation, meanwhile, worsens the impact of droughts and floods.18 Somalia lost approximately 4.9 per cent of its tree cover between 2001 and 2021.19 Demand for firewood and charcoal is the primary reason trees are felled.20 Most Somalis living in towns have charcoal stoves, while rural and nomadic populations use firewood for cooking.21

The combined effects of drought and deforestation have decimated farmers’ livelihoods and pushed hundreds of thousands to migrate to cities, while herders must travel longer distances to find pasture.22 The loss of tree cover also accelerates soil erosion and reduces the land’s capacity to retain water. Extreme rainfall is more likely to cause flooding in areas with thin or degraded forests.23 While some evidence suggests groundwater levels are rising in parts of the Horn of Africa, climate experts in Somalia note that dry soil becomes less capable of absorbing water, limiting the recharge of groundwater and aquifers that nourish plants and roots.24 Overgrazing creates additional stress on the soil, as livestock eat pastures bare and come back for more before the grasses have time to grow back. This phenomenon was exacerbated by the drought: Somali pastoralists, who follow a transhumant lifestyle, found that seasonal migration routes for their flocks were often blocked following clan disputes. Confined to a smaller number of ranges, livestock ended up degrading the land further.25

The confluence of climate shocks and environmental harm threatens Somalia’s hopes for stability, regardless of what happens in the state’s conflict with Al-Shabaab. That said, the conflict indisputably exacerbates these climate threats and places major obstacles in the way of efforts to address them.

III.Al-Shabaab and Somalia’s Drought

The climate shocks in Somalia in the last decade have much to do with the vicissitudes of Al-Shabaab’s fortunes. Like many insurgencies, Al-Shabaab has sought control of water and other natural resources to sustain its fighting capacity, generate revenue and exercise governance.26 During droughts in 2011, 2017 and 2020-2023, it used access to food and water as a weapon. Particularly in areas where it has been under military pressure, the group has deliberately worsened residents’ plight by damaging, destroying or poisoning water points. These practices predictably alienated many locals, which in turn ended up bolstering counter-insurgency efforts.

Conversely, the group has at times used its grip on resources to win hearts and minds. In southern areas where it governs with little resistance, Al-Shabaab has on occasion intervened to help locals struggling with the consequences of extreme weather. This kind of assistance nonetheless remains sporadic, displaying a selective and opportunistic approach to resource control.

A.Conflict and Natural Resources

1.Al-Shabaab and the environment

Al-Shabaab’s control of natural resources serves multiple purposes, including revenue generation, population control and the exercise of influence over local communities. Natural resources are at the heart of Somalia’s conflict. Both the government and Al-Shabaab understand the strategic importance of controlling water and land, which is vital in an arid to semi-arid country where most people rely on agriculture and pastoralism. During droughts or famine, water access becomes highly contested, fuelling tensions among clans and insurgents. Al-Shabaab exploits these frictions to strengthen its territorial grip and to extort money from those living under its control via illegal taxes and fees imposed on farmers and herders.27 (The Somali government, for its part, has also, on at least one occasion, weaponised resources by restricting water access in an area of central Somalia controlled by Al-Shabaab as part of its counter-insurgency strategy.28)

Exploitation of forests has ... formed part of Al-Shabaab’s revenue portfolio.

Exploitation of forests has also formed part of Al-Shabaab’s revenue portfolio. For years, the charcoal trade served to boost the group’s war coffers, with militants taxing exports to Gulf states.29 After the UN Security Council prohibited charcoal exports from Somalia in 2012, military pressure from an African Union mission to Somalia forced Al-Shabaab to abandon Kismayo, the capital of Jubaland and a strategic port.30 As a result, Al-Shabaab lost much of its income from charcoal exports.31 At checkpoints, the group continued to levy taxes on charcoal transported within Somalia. Still, UN sanctions monitors noted in 2019 that Al-Shabaab had stopped taxing the product and instead started sabotaging charcoal shipments, probably in a bid to undermine Jubaland’s export earnings.32

The group’s stance toward deforestation has fluctuated, however. In 2018, it prohibited tree cutting in zones under its control and banned single-use plastic bags, in the name of protecting the environment.33 In the coastal town of Xarardheere, about 500km north east of Mogadishu, Al-Shabaab reportedly planted thousands of trees when it was in control there.34 Observers say militants sought to maintain the forest cover in order to shield themselves from drone attacks.35

Access to water – perhaps Somalia’s most precious commodity – has proven a particularly useful way for Al-Shabaab to generate revenue and assert its authority over the population in areas it controls.36 In Jubaland, for example, militants charge herders 5,000 shillings ($0.50) each time a camel drinks from a trough.37 In Adan Yabaal, a town in the southern Middle Shabelle region which was under Al-Shabaab control between 2016 and 2022, the group managed several boreholes using diesel pumps to bring up water. A trader from Adan Yabaal told Crisis Group that Al-Shabaab expected residents to maintain the pumps but forced them to pay for their livestock’s water as well. Farmers from the Al-Shabaab-controlled town of Jilib must pay the militants at least $20 before they sow crops, regardless of how much land they are cultivating.38 Al-Shabaab then obstructs the flow of water to the fields of anyone who refuses.39

2.The military offensive and beyond

Following a protracted process to select a new leader, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud assumed the Somali presidency in May 2022. His return to power – he had been president before – coincided with mounting discontent with Al-Shabaab, particularly among the politically dominant Hawiye clan. In August 2022, a militant attack on a Mogadishu hotel that killed twenty persuaded the government to launch a fresh offensive against the Islamist insurgency.40 The federal army partnered with clan militias in regions that had already started to rise up against Al-Shabaab in order to dislodge the militants from central Somalia. Aided by U.S. airstrikes and other foreign support, the operation yielded the most comprehensive territorial gains since the mid-2010s, booting Al-Shabaab fighters out of areas the group had held for years.41 Much of the progress came down to local clan collaboration, while international ground forces, in particular the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), helped with supplies and logistics but did not engage in direct combat.

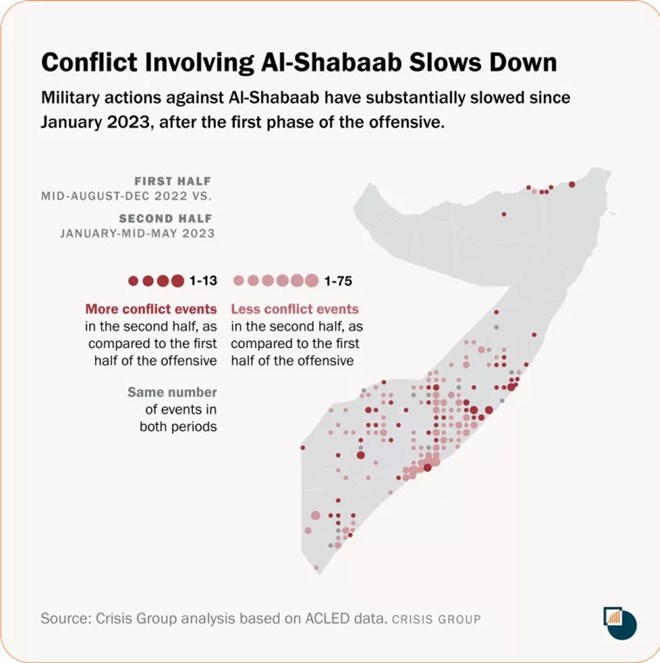

As a next step, Mogadishu planned to send soldiers into Al-Shabaab’s southern strongholds. But phase two of the campaign, which always promised to be more difficult, has stalled for now (see Figure 2 below).42 The government is still struggling to assign forces to provide security in recaptured areas and step up service delivery there, while distrust among local communities has hampered a unified effort against the militants. As a result, Al-Shabaab still holds large areas of rural territory in central Somalia and remains a significant threat.43

Plans approved in August by the African Union for a successor to ATMIS, the AU Support Mission in Somalia, would see a new 12,000-strong mission deployed to Somalia from January 2025 until as late as December 2029. The mission is meant to serve as a holding force that provides security in key urban centres and infrastructure such as airports, while Somali soldiers continue the offensive against Al-Shabaab.44

Figure 2

B.Al-Shabaab’s Reaction to Past Droughts

Al-Shabaab’s behaviour during climate crises has done huge, lasting damage to the group’s reputation. In both 2011 and 2017, during catastrophic droughts that led to famines, the insurgency imposed harsh restrictions on movement and access to aid, costing itself considerable local support.

The drought and famine in 2011 coincided with an offensive by the predecessor to ATMIS, the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), in which Al-Shabaab lost territory and U.S. drone strikes killed several of its leaders.45 Despite losing control of many towns and cities during this period, the group managed to keep its foothold in rural areas of south-central Somalia, largely by avoiding direct combat and infiltrating areas that were supposed to be under government rule. The group also weathered bouts of internal dissent, often employing repressive tactics to maintain a unified front and survive a leadership transition in 2014.46

Over this period, the group became paranoid about espionage and stopped foreign aid agencies and their local partners from delivering relief. Senior Somali politicians and aid workers blamed Al-Shabaab for the famine in 2011, which killed a quarter of a million people, mainly children.47 Domestic pressure eventually pushed Al-Shabaab to establish a coordination office later that year, however, allowing national relief agencies to distribute aid to people living under its control on the condition that the agencies provided documentation of their activities and paid the militant group as much as $10,000 in so-called registration fees, as well as additional “taxes”, depending on the type and size of deliveries or projects.48 Fearful of violating broadly worded U.S. counter-terrorism laws on providing material support to jihadists, many aid agencies declined to take up the offer, notwithstanding the hardships facing many who remained out of reach of assistance.49

Al-Shabaab granted international agencies more room to deliver aid during the drought that began in October 2016.

Al-Shabaab granted international agencies more room to deliver aid during the drought that began in October 2016 and ran well into the following year.50 Likely fearing a repeat of the 2011 calamity, and anxious to avoid the opprobrium it had earned then, the group also allowed people living in areas it controlled to seek aid in federal- and state-controlled territory.51 While the group heavily restricted both international agencies and most national agencies from delivering aid to its strongholds, it refrained from attacking them when they trucked supplies to government-held towns.52

Yet Al-Shabaab’s approach hardened again by June 2017, when it threatened locals with violence to stop them from getting aid.53 As Crisis Group reported at the time, Al-Shabaab worried about a mass exodus that could expose its fighters to intensified drone strikes and ground attacks, especially because drought conditions were severe in areas of southern and central Somalia that the group controlled.54

C.Al-Shabaab and the 2020-2023 Drought

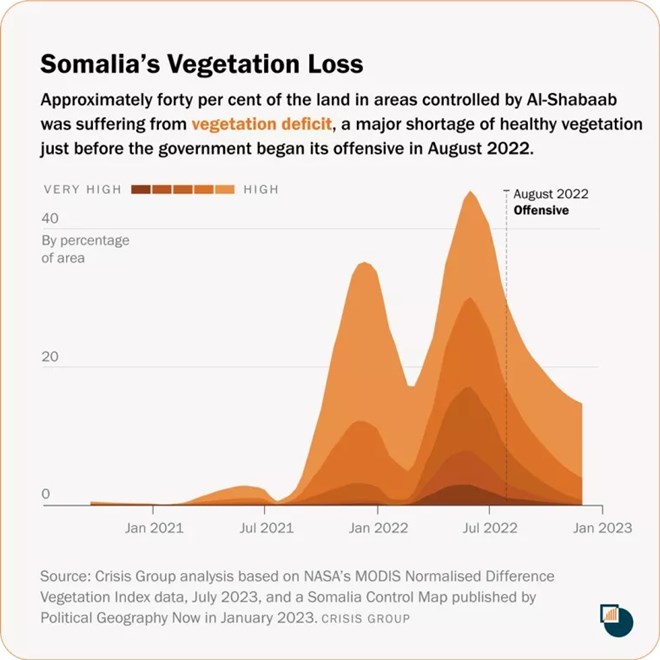

The parts of central and southern Somalia held by Al-Shabaab were hit hard again by drought between 2020 and 2023, as well as by flooding, fuelling displacement and weakening the group’s influence. In 2022, Al-Shabaab-administered areas received barely half of their average annual rainfall.55 Approximately 40 per cent of the land in areas controlled by Al-Shabaab in central Somalia were suffering from a major shortage of healthy vegetation just before the government began its offensive in August 2022.56

Figure 3

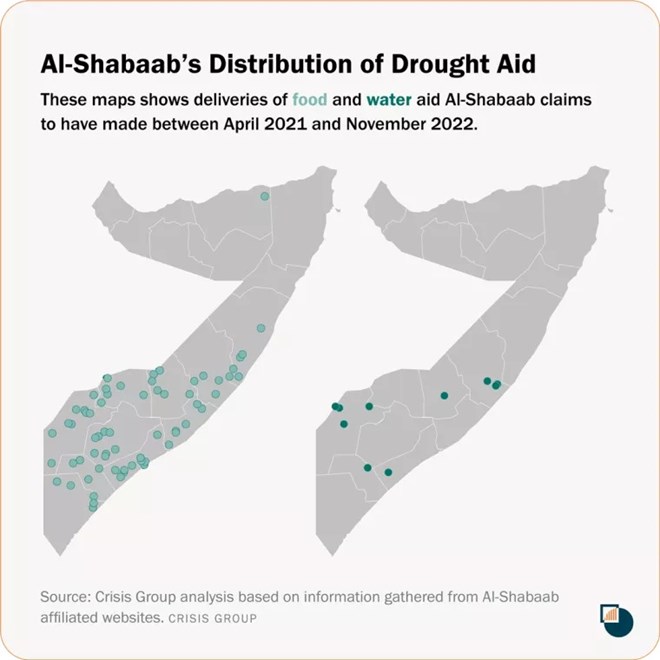

Once again, however, Al-Shabaab appears to have hurt its own standing with Somalis through its drought response. It delivered some supplies, but it was either unwilling or unable to provide substantial humanitarian assistance, despite establishing a drought response committee in 2021.57 Crisis Group recorded 127 deliveries of food and water claimed by Al-Shabaab in eleven regions between April 2021 and November 2022 (plotted on the map in Figure 4).58 But Crisis Group analysis of videos posted by Al-Shabaab suggests that the deliveries were as much a propaganda exercise as a genuine attempt to ease food shortages.59 In the videos, the camera often zooms in on aid recipients cursing “infidels” and attending religious lectures. Overall, it was assistance from international partners that did the most to avert famine during the drought.60

Figure 4

Overall, in fact, Crisis Group research shows that Al-Shabaab’s actions during the 2020-2023 drought worsened conditions for the population.61 Despite the drought’s severity, the group maintained blockades in towns such as Wajid, Hudur, Qansadheere and Dinsor in south-western Somalia, making it difficult for residents to seek aid.62 One mayor told Crisis Group that residents were punished for refusing to use Al-Shabaab’s justice systems or pay its “taxes”.63 Militants also imposed taxes, barricaded strategic roads and destroyed supplies of food and water. Such behaviour fuelled resentment of the insurgents among the population, above all in central Somalia.64 As clans in that area mobilised militias to fight Al-Shabaab, the federal government saw an opening to reclaim territory from the militants. Soon thereafter, it launched a major offensive against the group.

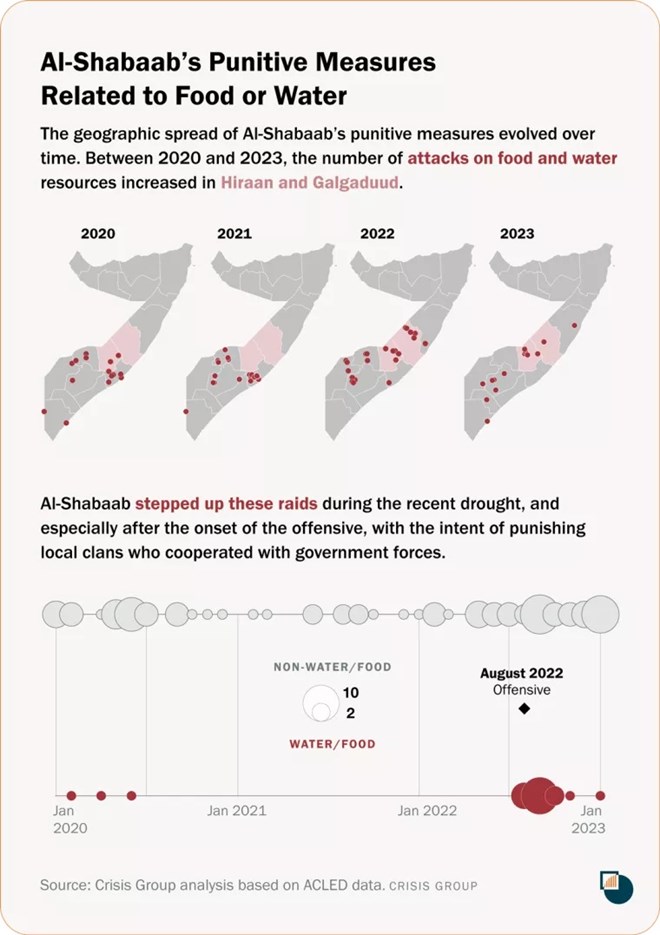

In response to the 2022 offensive, Al-Shabaab intensified a pre-existing pattern of attacks on water points and other infrastructure, most likely as a way to punish local clans for cooperating with government forces.65 This escalation included atrocities afflicting Hawadle civilians in Hiraan, which took place shortly after the clan began resisting Al-Shabaab. In early September 2022, for example, Al-Shabaab launched a brutal assault in Hiraan, killing at least nineteen Hawadle, including women and children.66

This same pattern had been identifiable throughout the drought: Crisis Group identified at least 65 attacks on both convoys carrying food supplies and wells between October 2020 and December 2022, nearly twice the number that had occurred in the two previous years.67 The attacks also took place over a wider geographic area: Panels C and D in Figure 5 above show raids on food and water supplies in Hiraan and Galgaduud between 2022 and 2023.68 But, as the Figure 6 below indicates, militants stepped up such attacks during the offensive that the government began in August 2022.

Figure 5 and Figure 6

Growing fury among local communities over these punitive measures has nevertheless led the group to adopt a slightly more flexible approach since late 2022. This approach has included renegotiating terms for humanitarian access with certain clans and communities in southern Somalia to dissuade them from joining the government offensive. In the Bay region of South West state, for example, Somali employees of an international NGO told Crisis Group that they were able to enter villages close to Al-Shabaab-controlled territory from late 2022 onward, apparently with the group’s tacit consent.69 In Garasweyn, near Bakool region, around 200 households received relief, including biscuits, dates, cooking oil and milk as well as mobile money transfers.70 A Somali NGO told Crisis Group that Al-Shabaab reached out to local businesspeople and elders in 2022 to request that they help people displaced by the drought with water and cash. The NGO declined to assist due to donor restrictions on engagement with Al-Shabaab.71

The change of tactics may partly be a consequence of worsening hunger and disease within Al-Shabaab’s own ranks. Aid workers and security officials reported that fighters and their families in the Al-Shabaab-controlled Gedo and Bay regions looked thin and physically weak.72 Male defectors reportedly told Somali security forces that they survived on a single portion of white rice per day.73

Other evidence indicates that community pressure – and concern about resentment of the group among clans – helped soften Al-Shabaab’s stance toward aid deliveries. Previously, insurgents would regularly make threatening telephone calls to prominent citizens with connections to relief projects in Bay and Bakool regions, but these calls stopped in August 2022.74 The group has also offered food to communities in central Somalia and parts of the southern Jubaland state, or agreed that militants will not openly carry weapons in urban areas.75 Some humanitarian workers are hopeful that Al-Shabaab will eventually relax its restrictions on aid further.76

International efforts to negotiate consistent access to people living in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas have largely failed.

That said, Al-Shabaab continues to resist outside humanitarian assistance. International efforts to negotiate consistent access to people living in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas have largely failed.77 The group seems determined to restrict the movements of both Somali and foreign NGOs, mostly limiting aid to medical care and cash transfers through local intermediaries, or demanding “taxes” of up to 40 per cent on the assistance or cash that is to be provisioned – the latter a condition that foreign aid workers are typically unwilling to meet.78 The paranoia about outsiders has persisted. In 2022, Al-Shabaab killed Somali contractors working on water projects funded by international donors.79

These same tensions are visible in Al-Shabaab’s treatment of water provision. Al-Shabaab’s attacks on water supplies have continued, representing a deliberate attempt to undermine the efforts of central and local governments to provide essential services. Between January and February, the group claimed responsibility for at least eighteen attacks, including several on water trucks using improvised explosive devices.80 Attacks on 20 and 24 January destroyed water trucks in Afgooye and Bossaso (Puntland) regions, respectively, with no casualties.81 A subsequent attack on 15 February hit an ATMIS convoy travelling between the villages of Bular Mareer and Golweyn, destroying another water truck and reportedly killing three soldiers.82

At the same time, Al-Shabaab occasionally builds water infrastructure itself. In 2020, for instance, the group oversaw the construction of a well in Qudus, about 40km from Kismayo.83 The militants also transported drilling equipment from Mogadishu to Tiyeeglow, a district in the southern Bakool region, where contractors working for the group reportedly dug wells in forested areas.84 In Buulo Fulaay, a town Al-Shabaab controls in the southern Bay region, the group built a reservoir. In May 2023, Al-Shabaab released a video featuring the reservoir, with supposedly prominent locals saying the nearest alternative water source was 60km away.85 An Al-Shabaab leader also spoke of plans for similar reservoirs elsewhere.86 Using satellite imagery, Crisis Group confirmed the construction of a reservoir, a canal and a water tower in Buulo Fulaay, and verified work in three locations where Al-Shabaab claims to have rehabilitated canals.87

Local water needs have, at times, served as avenues for negotiation with Al-Shabaab. In 2020, residents in Afmadow district in Lower Juba region wanted to dig wells with money collected from the diaspora. The government controls Afmadow town, but Al-Shabaab retains sway in the surrounds. At first, Al-Shabaab refused to grant permission for villagers to dig a berkad, a large cistern or shallow reservoir that collects rainwater, before letting them do so.88 In 2021, a Somali aid organisation built a sand dam in Gedo region after residents persuaded Al-Shabaab that the barrier, which helps store water during droughts, was important.89

D.Displacement in Southern and Central Somalia

As mentioned above, climate change, drought and Al-Shabaab’s harsh governance are driving displacement. Somalia ranks among the countries with one of the highest populations of internally displaced persons globally.90 According to the UN, an additional 228,237 people have been displaced since April, due to flooding, drought and conflict.91

A camp for the displaced, a place of urgent need, Baidoa, Somalia. 12 September 2022. CRISIS GROUP / Nazanine Moshiri

Several people told Crisis Group that they fled Al-Shabaab’s rule because they could not meet the group’s onerous tax demands, because they did not have enough food or water, or both.92 It is unclear if Al-Shabaab has a singular policy on movement in and out of its territory, but its policies are generally restrictive. At times, the militants have allowed residents to move in and out of the areas they control. On other occasions, militants have stopped men from leaving, perhaps because they could be recruited to fight. Displaced people in Baidoa and Dollow told Crisis Group that they were afraid of being imprisoned, tortured or killed if caught leaving Al-Shabaab territory.93 Most escaped detection by leaving in small groups or travelling under cover of darkness. Some discreetly moved their children out of militant territory one at a time.94

Those who manage to leave Al-Shabaab territory and secure shelter in a camp for displaced people face dire conditions. An overwhelming majority of Somalia’s displaced are women and children – men often want to stay behind to look after the family property or are prevented from leaving by Al-Shabaab.95 Life in these camps is precarious for many people, with donors rightly putting the needs of pregnant women and infants first when distributing food and other necessities. Moreover, gendered divisions of labour, which hold women responsible for tasks like fetching firewood outside camp, mean that women and girls are exposed to sexual violence that is generally perpetrated by men acting individually or in groups. Resources for sexual and reproductive health care are lacking.96

An older woman sits in a camp for the displaced in Baidoa, Somalia. 12 September 2022. CRISIS GROUP / Nazanine Moshiri

IV.Tackling Climate Change’s Ill Effects

Somalia will continue to face extreme weather in the foreseeable future, while its capacity to cope with climate disasters is among the lowest on the planet.97 On its own, the Somali government has neither the money nor the technical expertise needed to deal with its most pressing problems. In December 2023, Somalia secured $4.5 billion in debt relief under an International Monetary Fund program for poor countries, which should help it invest more. But the country still needs an estimated $5 billion annually to address climate change, and it used the COP29 summit in Azerbaijan as an opportunity to seek more funds.98

Foreign partners, meanwhile, have sought to alleviate acute humanitarian crises caused by droughts and floods rather than develop long-term strategies that could help the government fight climate change, such as investing in water infrastructure or supporting agriculture and pastoralism. In large part, they have chosen the short-term priority because the aid flows are not generous enough to address both.99 On top of that, widespread corruption related to aid deliveries means that scarce resources are already under great strain. In September 2023, a confidential UN report revealed cases of extortion of cash assistance in 55 displacement camps.100 Critics of fluctuating humanitarian relief argue that this pattern of aid disrupts long-term local peace efforts and draws communities toward overcrowded areas where resources are constantly running low.101 They have proposed redirecting a larger proportion of aid to projects that can bolster Somalia’s resilience to climate shocks.102

A newly arrived displaced family is setting up camp in Baidoa, Somalia. 6 March 2023. CRISIS GROUP / Nazanine Moshiri

A.The Quest for Climate Funds

Like many countries riven by conflict, Somalia struggles to get access to climate financing.103 In 2009, wealthy nations pledged to provide $100 billion annually by 2020 to help developing countries cope with climate change. That amount falls well short of the trillion dollars needed to respond to global needs.104 Even then, rich countries are not honouring their promises, while the distribution of climate funds remains grossly unequal. On average, countries grappling with climate change and conflict receive only a third of the climate financing per capita compared to countries at peace.105 At the COP29 summit in Baku, negotiators pledged $300 billion per year by 2035 to improve climate finance access for vulnerable nations like Somalia, but this sum still falls far short of what is required to meet adaptation needs.106

Somalia’s government is well aware that it needs to protect the country from floods and droughts. But while donor funds have been slow to arrive, things are tentatively heading in the right direction. In 2021, Somalia’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change obtained $2 million indirectly from the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a fund based in South Korea that is part of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, to help communities adapt to increasingly severe weather caused by climate change.107 In October, the GCF signed an agreement with UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Somali government for a $95 million climate resilience project, which it says will benefit around 1.2 million Somalis nationwide.108 Denmark, for its part, has pledged $150 million to Somalia over the next five years, with approximately 40 per cent of this amount earmarked for conflict-sensitive climate adaptation projects.109 Somalia may also lobby for bilateral climate resilience funding from the Gulf states.110

B.Managing Water, Fixing Infrastructure and Regenerating Land

Somalia’s outdated water infrastructure urgently requires investment if the government wants to build resilience to climate shocks. Piping is antiquated, and most of the country’s irrigation and flood control structures date back three decades, leaving it ill prepared for floods.111 Years of conflict, deforestation and lack of maintenance have eroded river embankments and barrages, as well as filled canal systems with debris and soil. Drainage systems have silted up. Farmers often breach riverbanks to alter water flows in order to irrigate their crops.

The government, with donor assistance, has already tried to alleviate irrigation and infrastructure problems, but Al-Shabaab’s presence has frequently delayed or blocked these efforts.112 There are opportunities for delayed resilience projects to move ahead, however, as the military offensive has improved security in towns whose surrounds were previously too dangerous for authorities to work in long-term. For example, in Jowhar, the capital of Hirshabelle state, authorities want to rehabilitate irrigation and flood control infrastructure, which would enable canals north of the town to collect floodwater from upstream regions. The water could then be stored in a reservoir in Balad, to the benefit of hundreds of thousands of people.113

Another challenge is the dearth of hydrological and weather data in many regions throughout Somalia. The government lacks both the funding and personnel to establish additional weather stations and water monitoring systems.114 The paucity of data makes it difficult to determine the appropriate depth for boreholes, for example, an issue made all the more important by the fact that many wells have run dry, particularly in farmlands near rivers. The shallow water in other wells is often saline and unusable.115

Still, the authorities are taking steps in the right direction. The Ministry of Energy and Water Resources is developing policies to improve water resource management, with the aim of developing local expertise to respond to droughts and floods, create warning systems and build flood defences and water catchments for dry spells.116 The Somalia Disaster Management Agency, meanwhile, is working with the World Bank and UN agencies to prepare for the impact of heavy rainfall and flooding.117 For example, Somalis, including those living in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas, receive flood risk warnings via an automatic ringtone mobile message.118

Tensions between Mogadishu and federal member states around climate resilience measures do not make matters easier.

Tensions between Mogadishu and federal member states around climate resilience measures do not make matters easier. The latter often complain of the central government’s interference, feel they are not consulted or do not receive any development projects. The GCF-funded project highlighted above will be executed in all federal member states, including Puntland.

Some donors, for their part, are investing in drilling to pump underground water. A project started by Ruden Energy, a Norwegian company, that the Somali government is now handling with the support of the UN, is assessing how much water the country has deep underground.119 This water is typically in aquifers anywhere from 500m to a few kilometres below the surface. These aquifers can safeguard water from pollution and contamination and are, in some cases, less susceptible to immediate climate fluctuations, as they rely on precipitation that could be millions of years old. Somalia’s deep aquifers are replenished by rainfall hundreds of kilometres away in the Ethiopian highlands.120 In tandem, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, with Somali government backing, is gauging the environmental, socio-economic and conflict risks of this deep drilling project.121

C.Handling Conflict Risks

Handling conflict risks and involving communities in planning water projects in Somalia has not been straightforward. In the case of one irrigation project in the Marka/janale region that began in 2021, the FAO and the International Organization for Migration helped create water management committees bringing together feuding clans, with members including women and young people.122 Progress was slow, however. Despite protection from Somali soldiers for local contractors, Al-Shabaab militants threatened people and hid improvised explosive devices along a canal. They also took people connected to the project hostage, holding them for three months.123 The $4 million, EU-funded project was eventually completed in March 2023, giving around 3,000 families, including people who live in Al-Shabaab-controlled areas, access to water for farming.124

Officials involved in this and similar initiatives, such as the projects in Galmudug and Hirshabelle known as the Deegan Bile, say donors and communities have drawn many lessons from their experiences. Dialogue with local communities and clear, agreed norms for managing natural resources tend to reduce conflict risks. They can also enhance local authorities’ legitimacy by linking them with informal governance mechanisms and improving the delivery of essential services.125

Several international organisations working with Somali partners have even relied on local networks and, at times, used intermediaries to negotiate with Al-Shabaab in their attempts to ensure that aid reaches vulnerable people despite inhospitable security conditions. These initiatives include the Somalia Resilience Program, a collective effort of seven international and national NGOs, which has raised $151 million since 2012.126 It provides cash aid during flooding to vulnerable people, including women, and focuses on relocating farmland and constructing long piping for irrigation systems. Similarly, the Building Resilient Communities consortium has invested heavily in water access and drought resilience.127

V.Ways Forward

The overlapping challenges of conflict and climate change are major causes of death and displacement in Somalia. Ideally, the Somali government should swiftly establish its presence in communities liberated from Al-Shabaab rule, working alongside international partners to improve the lives of locals. Donors should also support humanitarian organisations that undertake climate adaptation projects through local NGOs or private contractors.

With the Somali government’s offensive against Al-Shabaab stalling, however, it is unlikely that the group will cede territories it controls, leaving hundreds of thousands of people vulnerable to weather shocks and exposed to predation at the militants’ hands. The government is therefore in a tight spot. Defeating Al-Shabaab by force of arms is proving elusive. Abandoning these communities to the group’s control could entail dire humanitarian consequences. On the other hand, contact between national or state officials and Al-Shabaab seems unrealistic for now and potentially hazardous. Direct negotiations between local officials and the group over issues such as water-related relief could inadvertently legitimise Al-Shabaab’s rule, especially if the group were able to portray itself as a public service provider.

The government will inevitably need to tread carefully. Given Somalia’s dire climate projections, strengthening funding for building resilience to extreme weather might offer a less contentious and more effective way to establish trust between Al-Shabaab and the government, perhaps laying the groundwork for eventual dialogue as a means of winding down the conflict. In the meantime, the government should enhance water and resource management in areas it controls.

A.Boosting Aid for Climate Resilience

The continued danger of Al-Shabaab and the cautious approach of climate donors, motivated in part by concerns about corruption, are slowing down Somalia’s progress on climate adaptation. Over the medium to long term, international donors should look to support climate resilience projects like the GCF-funded adaptation project, which could help break Somalia’s dependence on aid. Large-scale water harvesting projects that take care not to harm the ecosystem should be the top priority.128 Initiatives should include flood barriers that encourage tree planting along riverbanks, which mitigate environmental degradation and enhance flood resilience.129 Projects such as the aforementioned offstream canal in Jowhar in Hirshabelle could help the country better withstand climate-related shocks. Donors could also boost Somalia’s climate expertise, for example, by offering grants to Somali students at top water engineering faculties.130

Crisis Group’s Nazanine Moshiri and Omar Mahmood speak to a displaced woman who has been given farming land and water through a World Vision and the World Food Programme project in Dollow, Somalia. 9 September 2022. CRISIS GROUP

Another option is incorporating climate and environmental expertise into humanitarian relief and development. Given the expected decline in humanitarian aid available to Somalia due to crises in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan and elsewhere, UN agencies and other international aid bodies should be more flexible, coordinate better and share resources with local NGOs.131 They should ensure that water scarcity and related humanitarian challenges are addressed through more durable solutions that also consider conflict and environmental risks. One way to do so is by investing in hydrological surveys and conflict-sensitive projects to store and harvest water.132 In following this course, they should ensure the government creates opportunities for women to shape climate adaptation strategies by sharing their needs and expertise with decision-makers.

Serving communities hit by drought, flooding and conflict also requires improving livelihood opportunities and other services such as sexual and reproductive health care. The UN and international NGOs should help the government provide more displaced people with cash transfers to pay for housing, enabling beneficiaries to choose to stay in cities if they want to seek work there. With donor support, the government should improve access to prenatal and maternal health services, especially in rural and displaced areas, by deploying mobile clinics to reach remote communities. To help herders stay in rural areas, donors should help regenerate degraded land and develop crop varieties that can survive harsh temperatures and droughts.

The government, for its part, also bears its share of responsibility in ensuring that foreign aid reaches Somalia and achieves its intended goals. Above all, Somali authorities should also make fighting corruption a priority: some international donors told Crisis Group that they need to see more progress on this issue.133 More broadly, a major GCF donor noted that Somalia and other conflict-affected countries should bolster the state’s fiscal management, such as tax systems, in order to become credible loan recipients. Lastly, the Somali government should cooperate with civil society, community leaders and peace activists, including women, to gain better insights into how local communities could address climate and environmental change.134

B.Natural Resources in Liberated Territories

With the help of foreign partners, the Somali government should continue to restore basic services, including water access and food production, to newly accessible areas from which the army has expelled Al-Shabaab. These areas, some of which the militant group treated badly for years, are in desperate need. Data from REACH, a humanitarian initiative, has highlighted a steep decline in herders’ livelihoods in Xarardheere district in Mudug, which was under Al-Shabaab’s control until January 2023.135

Crisis Group’s Nazanine Moshiri and Omar Mahmood speak to South West State President Abdiaziz Mohammed “Laftagareen”, Baidoa, Somalia. 6 March 2023. CRISIS GROUP

While Al-Shabaab may have provided a degree of justice and security in some places, the government is far better positioned to facilitate international humanitarian aid after droughts or flooding, as well as essential social services such as health clinics and education. The government can also obtain foreign financial support for climate resilience and adaptation. By providing the means to meet communities’ water needs, the government can offer a sharp contrast to Al-Shabaab’s use of water access as leverage over local people. Water infrastructure may nevertheless be at risk of attack by Al-Shabaab, especially when the group is under military pressure or suspects that locals will resist its rule.

Somalis living in liberated areas would also benefit from the inclusion of water and livestock in efforts to establish better relations between sub-clans once Al-Shabaab is no longer in control and, thus, by extension, between communities and the state.136 As droughts and floods are likely to become more common, the government, along with the UN and local NGOs, could sponsor local dialogue over resource management, both during periods of typical weather and during droughts.137 As noted above, the Deegan Bile projects, which link climate action with local peacebuilding, reportedly strengthened local authorities’ legitimacy, especially in areas where the state’s presence rarely amounts to more than an army garrison.

C.Engagement with Al-Shabaab

Engagement with Al-Shabaab is already a reality for many Somali communities. Local communities can sometimes persuade Al-Shabaab of the importance of climate resilience projects. Local NGO staff on the ground in many of the most affected areas often communicate and sometimes negotiate with Al-Shabaab. In response, the government has on occasion arrested male elders for communicating or negotiating agreements with the militants.138 Instead, it should consider lifting its ban on engagement with the group. In the short term, communities should, where necessary, take steps to explore the possibility of dialogue with Al-Shabaab around relief from climate disasters and the development of sustainable water infrastructure. They should do so where the need is greatest and in areas where Al-Shabaab appears more attentive to the resentment that its heavy-handed tactics have stirred. Such engagement is also more likely to succeed in regions where militant leaders share clan affiliations with the local population.

Channels of communication to the groups could be initiated in various ways. After severe flooding, Al-Shabaab has shown greater willingness to alter its restrictions on humanitarian relief. Local communities could use this leniency to see whether the group would allow a surge in relief or the construction of more permanent flood barriers. In one concrete case, in the south-western city of Baidoa, business leaders and clan elders negotiated the lifting of an Al-Shabaab blockade in July 2023, for which the government did not punish them.139 Although the town is under state control, critical water sources remain in militant-held rural areas. Local leaders in Baidoa could, in the future, also explore deals with Al-Shabaab-approved contractors to drill boreholes in areas beyond government control, which would help refresh the town’s increasingly strained water supply.140

Even if the government consolidates its military gains ... Al-Shabaab will not be easily defeated.

Over the medium to long term, even if the government consolidates its military gains and goes on the offensive elsewhere, Al-Shabaab will not be easily defeated. Crisis Group has argued that the government should keep the possibility of negotiations open as a means of ending the war.141 The climate risks Somalia is facing could let the government find common ground with Al-Shabaab, if and when the time comes for political dialogue, and might even help ease tensions ahead of talks. The government and Al-Shabaab could, for instance, agree to ensure that relief supplies are delivered across territorial lines, under the guise of a humanitarian truce. The government might also tone down its rhetoric against Al-Shabaab by acknowledging mutual climate-related challenges.

The possibility of high-level engagement between militant and government leaders also depends on Al-Shabaab’s stance. Al-Shabaab has, in the past, rejected the idea of dialogue. Nevertheless, credible sources have indicated to Crisis Group that constituencies within the organisation may be more amenable to negotiations than its public statements suggest.142

Addressing climate resilience involves expensive, long-term projects that will require funding and security. In the interim, some communities might need to work with Al-Shabaab to find immediate water solutions. While these efforts may not necessarily directly involve the central government, they should at least have its implicit acknowledgement or consent. Climate shocks affect all Somalis, regardless of their stance in the conflict, and a cooperative approach involving all parties offers the best hope of a long-term solution.

VI.Conclusion

While droughts and climate change did not create Al-Shabaab or cause Somalia’s instability, they have shaped the environment in which the conflict is taking place and influenced the militant group’s tactics and evolution. Al-Shabaab’s behaviour amid a severe three-year drought showed its predatory characteristics and strategic manoeuvring – but also its vulnerabilities. In certain places, Al-Shabaab exacerbated the environmental impact of Somalia’s worst drought in decades, often deliberately through attacks on water supplies. The group’s harsh policies have driven displaced people out of its territory and contributed at least in part to a major backlash that has cost it control of parts of central Somalia. But even if Al-Shabaab’s grip weakens or a peace agreement is reached, the underlying threats posed by climate change will persist, potentially creating opportunities for the group or other armed outfits to exploit.

The responses of the federal government and international donors to the overlap between climate shocks and armed conflict will be crucial to curbing violence, meeting Somalis’ basic needs and preparing for a future of increasingly volatile weather. Boosting foreign aid for climate resilience is vital, particularly if the assistance improves natural resource management and builds long-term solutions to climate shocks. Secondly, restoring essential services and empowering communities in liberated areas will help stabilise regions as the government re-establishes control. Finally, engagement with Al-Shabaab, while inevitably contentious, could pave the way for immediate relief efforts and lay the groundwork for future dialogue on shared climate risks.

There is a risk that government inaction or acknowledgement of community negotiations with militants over essential resources might unintentionally strengthen Al-Shabaab. Yet, given the protracted conflict, the government must consider alternative strategies to achieve peace and ensure public well-being. If it does not, it risks leaving Somali citizens exposed to the ravages of flooding, disease and famine.

Nairobi/Brussels, 10 December 2024

Appendix A: Map of Somalia

Appendix B: Data and Methodology for Charts and Graphs

The notes below explain the methods Crisis Group used to prepare the graphs and data maps featured in this report.

Figure 1: Precipitation anomalies – time trend and maps

The time trend and maps delineate precipitation anomalies in Somalia based on the Climate Hazard Centre’s CHIRPS rainfall data at a spatial resolution of approximately 5km.

The time trend displays the country area’s share affected by precipitation deficit (orange) or excess (blue) between 1990 and 2022. Z-scores are considered at the pixel level, comparing each month’s precipitation to the average of the same month of previous years, 1990-2022. Z-score = (meani m y –mean_baselinei m) / (sd_baselinei m +0.01), with i, m and y denoting the pixel, month and year, respectively. A small value of 0.01 is added to the denominator to avoid high Z-scores in areas with low inter-annual precipitation variability. Next, the sum of pixels with Z-scores below or above 1 is summarised to derive the country’s share affected by rainfall deficit or excess in a given month.

The maps reflect the April to June (Gu) rainy season rainfall anomalies of 2011, 2017 and 2022, respectively. Instead of considering anomalies on the month level as for the time trend, Z-scores are calculated for a given Gu season. In other words, the maps compare observed precipitation levels of a given Gu to the Gu average of previous years, 1990-2022. Z-score = (meani, Gu y –mean_baselinei, Gu 1990-2022) / (sd_baselinei, Gu 1990-2022 +0.01), with i and y de- noting the pixel and year, respectively. Anomalies are displayed on the pixel level.

Figure 2: Al-Shabaab conflict – map

Conflict events, based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) generate a map of conflict events involving Al-Shabaab. ACLED event counts over the first months of the government offensive (mid-August to December 2022) and the subse- quent months (January to mid-May 2023) are aggregated to the 25km grid cells. To reduce the risk of systematic measurement errors, only events classified as “battles”, “riots”, “violence against civilians”, or “strategic developments”, with geo-precision 1 or 2, and with one of the actors being Al-Shabaab are considered. Subtracting the number of events between mid- August and December 2022 from those between January and mid-May 2023 yields a com- parative measure of Al-Shabaab activity in a given grid cell.

Figure 3: Vegetation deficit – time trend

MODIS NDVI data at a spatial resolution of approximately 1km from NASA generates a time trend showing vegetation deficit patterns in Somalia.

The time trend displays the share of the country area affected by negative vegetation anoma- lies from the beginning of the drought in October 2020 to December 2022. Z-scores are con- sidered at the pixel level, comparing each month’s NDVI value to the same month of previous years, 1990-2022. Z-score = (meani m y –mean_baselinei m) / (sd_baselinei m +0.01), with i, m and y denoting the pixel, month and year, respectively. A small value of 0.01 is added to the denominator to avoid high Z-scores in areas with low inter-annual variability in vegetation density. Next, the sum of pixels with Z-scores below -1 is summarised to derive the country’s share affected by intense vegetation deficit in a given month.

Figure 4: Drought relief measures – maps

Crisis Group collected drought relief data from videos and photographs posted on Al-Shabaab- affiliated websites, including Somalimemo. Verifying the accuracy and completeness of Al- Shabaab’s alleged aid efforts is virtually impossible. Dark green dots represent the distribution of water; light green dots represent the distribution of food.

Figures 5 and 6: Punitive measures – maps and time trend

Maps depicting conflict events associated with punitive measures taken by Al-Shabaab against the population by the year (2020-2023), based on data from the Armed Conflict Loca- tion & Event Data Project (ACLED). Desk research and manual cross-checking revealed that ACLED events with the following characteristics include relevant events: Al-Shabaab is listed as an actor, and the event type is classified as “Strategic developments”, sub-event type “Looting/property destruction” or event type “Violence against civilians”. Moreover, only geo- precision 1 or 2 events are considered to ensure map location accuracy. In a subsequent step, event notes are manually checked to remove false positives and categorised into “food- or water-related” and “other” punitive measures based on the information provided in the vari- able “notes”. The maps only show events related to food or water.

The time trend is based on the same data, showing the number of punitive measures in Hiraan and Galgaduud monthly from January 2020 to April 2024. Red dots represent punitive measures related to food or water, and grey dots represent all other events. The bigger the dot, the higher the event count in the respective month.